|

Polish Intelligence 1939-1945

There is a ‘Polish Military Tradition’ (Davies, 2001) that dates back centuries that is different to other nations due to Poland’s different periods of occupation and partition as a state. As Davies observed, Poland provided not only an arena for Europe’s wars, but also men as ‘cannon fodder’ under the colours of other nations. The military establishment lay semi dormant since 1717 since neither the Prussians, Russians or the Hapsburg’s wanted any sizeable independent army within territories that were once Polish. Indeed, the Russians disbanded the Polish Army after the November Rising 1830-1831 after Polish officers in a military academy in Warsaw revolted against Russian rule. However, Poland had a history of providing professional soldiers that made up the Napoleonic Polish Legions (1797-1802), the Army of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1813) and the Polish Army of the Congress Kingdom (1815-1831) that also established links to French culture, education and military studies.

Poland had not existed as an independent political entity since 1795 and the Partition Wars between Russia and Austria carved up territory through the Congress of Vienna in 1815. There were no permanent military institutions or professional traditions from which the country could draw upon since their Prussian, Russian and Austrian masters had very different approaches and philosophies to military standing and planning. Poles had long dreamed, schemed and plotted for the re-emergence of their independent country (Davies, 200; Kochanski, 2012). Networks of underground organisations existed within military circles. Major General Sosabowski in his memoire hints to the extent of them. ‘Buried in a garden in a small villa in the Warsaw suburb of Zoliborz there lies a rusting sabre. Perhaps it is still possible to read on the pitted blade the inscription ‘For honour and glory’. It was presented to me in 1912 by my men of the Underground Movement’ (Sosabowski 1960:11).

Piłsudski’s Polish legions (1914-1917) in Austria, the Polnische Wehrmacht (Germany) and Haller’s Polish Army (1917-1919) in France, provided a cadre of officers and men that eventually would shape Poland’s military in the inter-war years. Their military experience was mixed, but psychologically important for the re-birth of the Republic. Piłsudski had dabbled with the Union of Active Struggle (ZWZ) prior to the First World War and at the outbreak of war formed Polish Legions within the ranks of the Austrian Army that he thought would pave the way for an independent army. Although the legions were disbanded in 1917, observers ridiculed and challenged Piłsudski’s ability to form an effective army in a short space of time. Haller’s Polish army arrived in May 1919 acted as a morale booster as the new Republic tackled economic and financial pressures of an emergent nation who recognized the need to invest in military equipment and start production of weapons. The task of rebuilding Poland would appear daunting for those outside the region. During the period of partition, the socio-cultural and political structure remained largely intact in the provinces since foreign rule was by Berlin, Vienna and St. Petersburg distant and insensitive to local feelings where Polish authority lay in social and religious spheres (Davies, 2001). The landownership remained largely intact. The partitioning powers enabled Poles to be prominent in local government, the civil service and educational institutions. It was only the political authority that lacked moral fibre where unpalatable coercion enabled foreign rule. Polish life survived through a romantic vision of their moral and spiritual heritage.

With the rebirth of the nation, the military structure was modelled on France who had a prominent military mission based in Warsaw. The period as admirably captured in books by Alan Furst such as The Spies of Warsaw, Night Soldiers and The Polish Officer. The Polish Military Organisation (PMO) or the Polska Organizacja Wojskowa (POW) was probably the first organisation to clandestinely collect information in the East Prussian province since 1920s. The PMO participated in the plebiscites in Warmia, Masuria and Powiśle (Szymanowicz and Gołębiowski, 2009) that included arming the Masuria Guard which numbered some 6,000 members whose structure, and leadership was run by Polish Intelligence.

The Polish General Staff was divided into divisions based on:

- Oddział I (Division I) – Organization and mobilization

- Oddział II (Division II) – Intelligence and counterintelligence

- Oddziału III (Division III) – Training and operations

- Oddział IV (Division IV) – Quartermaster

The Polish intelligence services were born in October 1918 and subdivided into geo-political operational lines:

Sekcja I – Reconnaissance

Sekcja II

IIa (East) – Offensive intelligence for Bolshevik Russia, Lithuania, Belarusia, Ukraine and Galicia

IIb (West) – Offensive intelligence for Austria, Germany, France and the United Kingdom;

Sekcja III – General intelligence and surveillance abroad (East and West);

Sekcja IV – Preparation of a propaganda

Sekcja V – Contacts with military and civilian authorities

Sekcja VI – Contacts with attachés in Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Moscow and Kiev

Sekcja VII – Ciphers and encryption

An extensive network of foreign and domestic informants was quickly established through the émigrés and diaspora and those returning ‘home’ through post World War One Europe and Russia. The size of diaspora was over one million with large pockets in the German Ruhr valley and mines in northern France which later becomes significant in the preparation for the invasion of France. (Link to Operation Monika and Operation Bardsea)

The Polish-Soviet War 1919-20 blocked the advancement of the Communist Revolution into Europe. The Battle of Warsaw (or the Miracle on the Vistula) demonstrated Józef Piłsudski’s tactical skills both politically and militarily. The massive defeat of the Red Army had major ramifications through purges in the Russian military and politburo that would shape future events and outcomes in the imminent outbreak of war. For Poland, the nation had emerged, and politicians took note of the role the nation would play in central and eastern Europe. On 18th March 1921 the Treaty of Riga was signed through pressure from France and Britain in recognizing an independent Poland. The victory resulted in the reorganization of the intelligence services that remained in place until the outbreak of war in September 1939. The main changes were in Sekcja II that was reorganised in the way intelligence was handled, but more importantly in the early recognition of code breaking that was superior to Britain’s, France and the USA. “The knowledge of how a potential enemy was developing and deploying his military might made one’s own limited forces that much more effective. It was not a weapon that a newly reborn nation, especially one as vulnerable as Poland, could afford to neglect” (Budiansky, 2000 p. 69). (Link to Enigma).

Through much of the inter-war period and despite close ties to France, Poland did not share or collaborate with any of its allies on intelligence. The relationship between Poland and her allies were often strained through actions by Piłsudski and the formation of the Second Republic over border disputes. These disputes were complex and misunderstood (Davies, 2001) and Poland had won by force most of the disputes prior to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 that left many senior politicians in Europe concerned over Poland and her intentions. Piłsudski had envisioned a federation of independent states from Finland to Georgia to counteract Soviet intentions (Davies, 2001) and this notion raised concerns both amongst the allies, but also Germany and the Soviets.

Poland had been reading German Enigma traffic since 1933. As Germany had planned a coup in Danzig and retake the ancient city-port, Germany was testing the resolve of the allies and Hitler was seeking military triumph not an acquisition as in the case of the Czech capitulation (Budiansky, 2000; Davies, 2001). On June 30th, 1939, Lt. Colonel Gwido Langer, head of Biuro Szyfrow cabled his French and British counterparts to inform them of new events that required a meeting in Warsaw since meetings earlier in the year had been unproductive. Poland had an ‘ace up its sleeve’ in order for the allies to stand by Poland. At the meeting Major Ciezki, a cryptanalyst did discuss in general terms the daily settings of the Enigma machine and how these could be solved. Unknown to the delegates, the Poles had already resolved the Enigma settings and it was only the following day when a tour of the German Section based at Pyry, a small village a few kilometres south west of Warsaw did the full impact become apparent when the delegation was shown an Enigma machine and met the Polish cryptanalysts Rejewski, Zygalski and Rozycki. Copies of the machine were made available to the French and British. Despite a minor diplomatic incident involving the British delegate and cryptanalyst Alfred (Dilly) Knox who inadvertently insulted the Poles for withholding information, the long-term relationship throughout the war was unique between intelligence services. The degree of the British-Polish collaboration on intelligence has no other historic precedent (Andrews, 2005).

The structure of the Polish intelligence service remained throughout the war and this included the close co-operation between the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), (Link to Home Army, and SOE) and other sections of the military. Indeed, copies of cypher traffic held in the public records office in Kew indicates the scope of the services stretched from North and South America, Occupied France, parts of Africa and the Far East. The extent of the cooperation was not fully understood and today some files remain closed. However, on the publication of the

Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Commission on Intelligence Co-operation between Poland and Britain During World War II, the degree of cooperation was revealed. The reason for the ‘gap’ is due to the alleged destruction of records by SIS (Andrews, 2005). II Bureau was based on the French Deuxième Bureau under Colonel Leon Mitkiewicz (Andrews, 2005; Kochanski, 2012). Under the Anglo-Polish intelligence agreement of September 1940, the Poles agreed to pass all information to the British unless it was solely related to internal matters. Although, the AK had their own intelligence network, both HUMINT and SIGINT was passed via II Bureau to the British SIS that was essential for later operations led by SOE. The ability to collect an extensive range of intelligence through the SOE as an auxiliary arm came through forced labour (Organisation Todt), the AK and special operations in France such as Operation Adjudicate, Operation Monika and Desford or in Slovakia and Hungary. It is estimated in total some 45,770 intelligence reports from occupied Europe were processed by the Allies of which 48% were from Polish sources (Kochanski, 2012).

The size of the Polish intelligence network was 8 stations, 2 independent intelligence stations and 33 cells employing 1,666 registered agents (Kochanski, 2012). Neutral Switzerland acted as a conduit for intelligence traffic between the anti-Nazi head of the German Abwehr, Admiral Canaris and high-ranking officers in the German high command (Winter, 2011). For some time, it has been assumed the breaking of the greatest secrets of the Third Reich was based on signals intelligence (SIGINT) through the decryption of traffic through enigma code breaking at Bletchley (Budiansky, 2000; Davies, 2001) rather than human intelligence HUMINT. Winter (2011) suggested the use of at least two high-level agents within the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht and Oberkommando des Heeres, ‘Warlock’ and ‘Knopf' played a significant role in the access to German strategic and operational planning too. Warlock was caught and turned in 1940-41. Knopf provided vital information during the period 1942-43 but was compromised in the summer of 1943 through decoded communications of the Polish military attaché in Switzerland. This ‘discovery’ alters both knowledge of intelligence operations and post war perceptions of the Polish contribution.

It must also be noted that the Die Schwarze Kapelle (The Black Orchestra) were known to SIS and OSS through their activities and contacts in Switzerland where Halina Szymańska was acting as a go-between working in the Polish Legation in Bern. She regularly met with Admiral Canaris, the head of the Abwehr through working with Hans Gisevius a dissident known to Canaris and sent to Switzerland (Garliński, 1981) as a conduit for the anti-Nazi conspirators.

The Polish Government in Exile headed by General Władysław Sikorski brought together both the political and military heads that enabled Sikorski to be seen as the head of government while the initial head of state, President Władysław Raczkiewicz assisted in bringing the four main political parties: the Peasant Party, the Polish Socialist Party, the National Democrats and the Party of Labour together as a forum that included Jewish national minorities as the National Councili (Ciechanowski, 2005; McGilvray,2010).

Central to intelligence operations was the role the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) and the need to give Poland hope during the oppressive occupation in all aspects of Polish life. At the outbreak of war, there were numerous political parties whose origins were based on ‘private armies’ (Nowak, 1983) that left to act independently would threaten the long-term war efforts through in-fighting. The first task of the ZWZ and General Stefan Rowecki (Grot, Kalina) was to unite various factions and units under one command where some degree of independence would remain for political, social and recruitment programmes at local level (Nowak, 1983; Koskodan, 2009).

The Home Army Headquarters was divided into five sections, two bureaus and a number of other specialized units:

- Section I: Organization: personnel, justice and religion

- Section II: Intelligence and Counterintelligence

- Section III: Operations and Training: preparation for a nationwide uprising

- Section IV: Logistics

- Section V: Communication – including with the Western Allies and co-ordinating air drops with SOE.

- Bureau of Information and Propaganda or Section VI, formally known as Bureau for Political Information or BIP

- Bureau of Finances or Section VII

- Kedyw (acronym for Kierownictwo Dywersji, Polish for "Directorate of Diversion") special operations such as Action N

- Directorate of Underground Resistance

The Polish General Staff recognized it was inevitable that significant parts of Poland would be occupied by the Germans for an indeterminate time. The private armies and paramilitary leagues aligned to political parties would form the backbone of the planned guerrilla war, hence the need for unification under the direction of the ZWZ and eventually the Home Army (Armia Krajowa). The leagues included:

- League of Reserve Officers

- League of Young Pioneers

- League of Blind ex-servicemen

- Participators in National Rebellions

- League of Upper Silesian Rebels

(Source: Williamson, 2012)

II Bureau set up a regional structure for the planned partisan and guerrilla warfare that became active in July 1939 (of which my father, Zenon Krzeptowski became involved via the ZWZ). Five different groups would form the personnel (Williamson, 2012):

- Men 50-70 years old.

- Invalids and cripples unfit for military service.

- Women.

- Youths and children (many of whom had been in the Scouting and Guides)

- Specific personnel specially selected for their duties.

Recruitment of field agents and operatives had taken place prior to the outbreak of war and the intelligence service had identified targets in Poland, Hungary and Romania, particularly the transport networks that included the Danube. Suitable recruits had been found in the internment camps in Hungary and Romania and also those who had escaped to Scandinavia, Baltic states and other European countries. Diamond smugglers were recruited in Switzerland who had access to Germany and escapees in Holland and Belgium were recruited to deliver propaganda material (Williamson, 2012). These plans also included a feasibility of smuggling hardware up the Rhine.

The cell or each patrol would have a commander who had no ‘peace time’ connection with the others whose communication through code words and symbols-maintained security. Initially, recruitment concentrated in western Poland, Danzig and the Corridor by men who had been active in anti-German activities. Dumps for munitions and six training schools in sabotage that could train between 7 – 25 per week (Williamson, 2012) had been set up and were in place prior to the outbreak of war. Southern Poland was ideal for partisan and guerrilla warfare due to the terrain and experience of the clandestine war in Ruthenia in 1938 or the great forests on the East Prussian border. The Goralé or Highlanders had for centuries secret trails through the Carpathian Mountains whose knowledge was vital to AK and later SOE operations. The aim was for partisan raids over the German – Slovakian border targeting the Košice – Žilina railway with units of about 15 men. On the outbreak of war, units in East Prussia would attack railways, bridges and power installations in order to cause mayhem. The Poles sought British transmitters to improve communication and control even though II Bureau had not decided if the underground army would be under local command or under II Bureau. The German invasion and subsequent partition between Germany and Russia scuppered these ideas. General Juliusz Rómmel was tasked by General Tokarzewski to form the underground army made up of isolated fugitive soldiers and other local resistance organisations’ spread around Poland under the banner of the Service for Poland’s Victory (SZP) that was replaced by the ZWZ and later the AK. Conspiracy cells of 5 persons formed a network around geographic locations known as ‘posts’ whom had a local commander with combat or specialist units of 25 men. (It was the capture of a cell member that forced my father Zenon Krzeptowski to flee Zakopane on 15th May 1940). The life of a freedom fighter varied due to geographic location, leadership and access to communications, food and ammunition. Mazgaj’s (2009) enlightens the risks and hardships the freedom fighters of the Sandomierz Flying Commando Unit endured in war-torn Poland and is a worthy observation of actions and outcomes these units endured.

After 1939 the Polish people had limited income, education and access to religion or travel. The need for psychological warfare such as Action N was vital in wearing down German frontline troops in transit through Poland where ‘black propaganda’ was increasingly effective even though its origin was not known to the Germans or the Polish community (Nowak, 1989). A campaign of slogans appeared across Poland in order to undermine and divide German opinion to the extent that the Gestapo believed the black propaganda emanated from communists based in Munich (Nowak, 1989).

The development of trails and routes between the General Gouvernment, western Poland and Europe were established that enabled the AK and later SOE to operate extensively in occupied territories. The escape routes fell into four basic categories:

- Mass movement of volunteers which lasted from October to the end of December 1939

- Small groups organized by the Underground Movement during the first few months of the war

- individual escapes assisted by the Underground Movement throughout the war

- mass evacuation for re-enlistment (Anders Army)

The AK was recognised by Colonel Gubbins, head of SOE as an opportunity to develop European wide guerrilla operations since the fall of Poland had left agents in Hungary and Romania. These networks were also being used to facilitate the escape routes to the Middle East after the fall of France effectively blocked this route.

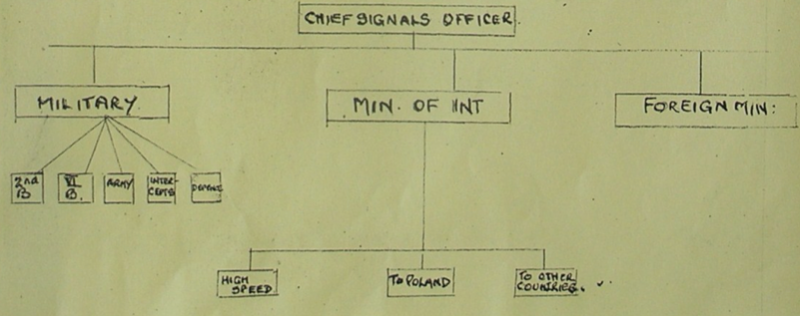

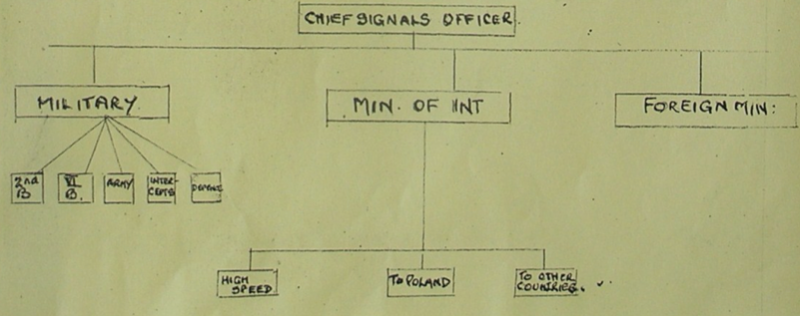

With the fall of France and relocation to Britain, there was a need to restructure both the military and intelligence to meet new challenges based on length of communications and integration of operations with the Allies rather than on French military structures. The GHQ was based in the Rubens Hotel in London. An Order on 30th August 1940 brought the General Staff, Polish Naval Command and the Airforce Inspectorate under the direct control of the Commander-in-Chief Sikorski. II Bureau was tasked to obtain information on armed forces, enemy states and third-party states and analyse their political, economic and military capabilities (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005). II Bureau was initially commanded by Col. Leon Mitkiewicz also came under the C-in-C through the Military Affairs Ministry covering the Polish Navy and Airforce. His lack of experience meant Lt.-Col. Gano took over the organisation, restructuring and operations while IV Bureau was under the command of Lt.-Col. Tadeusz Tokarz. II Bureau was responsible for the Intelligence Officers School and the offices of military attachés. Throughout the war these departments evolved and changed leadership due to the demands and need for personnel not attached to political factions within the Polish General Staff (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005). The Intelligence Department was sub-divided into sections:

- General: Personnel and translation work

- Central

- East

- Overseas,

- Intelligence Communications

- Offensive Counter-Intelligence

- Technical

(Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005)

The following table sums up the extent of the intelligence operations that grew or shrunk according to geographic, military and political needs.

| Section |

Stations and Networks |

| Central |

France, F-2, ‘300’, ‘Int’ - Paris; M – Madrid, P – Lisbon, S – Bern, Płn and L – Stockholm (later became SKN), ‘Afr’ – North Africa

Size: 5 stations, 2 independent intelligence stations, 20 cells with 34 officers, 1 NCO, 2 Officer Cadets, 23 civilians and 1 private. 378 agents.

|

| East |

R – Bucharest, J – Belgrade with single cells in Zagreb and Istanbul. Later in 1940 R closed and moved to Istanbul.

Wudal and R was based in Moscow. Later ‘Zadar’ and ‘Nora’ were set up.

Station ‘Bałk’ in Istanbul, ‘Tusla’ and Tandara’ in Romania were closed due being compromised.

T – Jerusalem.

Size: 23 agents, 40 informants run by Lt. Jozef Piekosz and a civilian employee Halina Bobińska.

|

| Overseas |

Had different duties and a different organisation acting as a link to OSS – American Intelligence.

Station ‘Estezet’ was based in New York and covered North and South America.

Staffed by 6 officers and 6 civilians and after mid 1944 had 2 independent stations. Size: 19 agents and 21 informants at their disposal.

|

(Source: Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005)

While II Bureau was fiercely independent of the Allies influence in directing their operations, they continued to develop their own ciphers that gave them a unique status amongst the allies. Operations in the field were more complex. Station F-2 consisted of both Poles and French largely based in northern France around the mining industry. There were some 250 agents that swelled to 2,800 by the end of 1944 (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005). These operations were very separate from SOE’s activities in Operation Bardsea and Adjudicate. (Link to Adjudicate) Heads of stations ran the agents who ran the informants while couriers ‘ran the gauntlet’ between stations. Communications were managed by the Polish Ciphers Section, Correspondence Central, Radio Intelligence who monitored traffic and the Foreign Ciphers Office all of whom were transferred to the Chief of Polish Ciphers Section post January 1942. The reason lay in tightening procedures and security in II Bureau that also assisted in speed in deciphering traffic. Communications control operated out of a base in Stanmore near London while training was based at the Intelligence Officers School initially based in London’s Ruben Hotel in Victoria and then moved to Glasgow. The location in Glasgow was most likely the West End in the Hyndland area of the city. Communication shortages, poor equipment and training limited II Bureau’s effectiveness and consistency in results. Despite these limitations the volume of reports passed to the allies was phenomenal and today on reflection wonder what more could have been achieved. Brig-Gen. Hayes A. Kroner praised the Poles in a meeting with General Sikorski that “The Polish Army has the best intelligence in the World. Its value for us is beyond compare. Regretfully there is little we can offer in return” (cited by Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005: 90)

Offensive Counter Intelligence was run by Captain Rudolf Plocek and staffed by 2nd Lt. Wincenty Tarnawski, Corporal Tadeusz Filip and two female civilian employees: Zofia Sarnowska and Bridget Todd. They were tasked to pass intelligence received from the allies and assess foreign intelligence activity and their methods. They also monitored hostile intelligence cells and hostile foreign states that required close cooperation with the Allied counter-intelligence. Much of their work was internalised keeping dossiers on II Bureau officer, members of the Sanacja and communist sympathisers. Some of their work included interrogating operatives returning from the field to ensure the network was not compromised in any way.

Counter-intelligence was also covered by the Polish Ministry of National Defence that was the main counter-intelligence department or CID. They had units attached to all parts of the Polish Armed Services. They were interested in those arriving in Great Britain as evacuees particularly those who had been under German occupation or had been recruited by the Soviet NKVD. Much of their work focussed on anti-subversive activity of the communists and their sympathisers. This section interviewed my father Zenon Krzeptowski on his arrival in Blackpool in January 1942 about any connections to the Goralenvolk party led by his uncle Wacław Krzeptowski’s. It was only a family connection, not political.

The Technical Section was set up in June 1943 and led by Lt. Konstanty Szałowski and staffed by 2nd Lt. Kazimierz Zielinski, Staff Sargeant Julian Stefankiewicz and Staff Sargeant Jozef Blinek who was supported by Corporal Stanisław Zalewski and a civilian employee Wacław Jarmułowicz. The section was tasked with technology, photography and for the development of intelligence chemistry such as invisible ink and forging documents. Translation work was done by a special sub-section led by Lt. Stefan Kucharski. They relied heavily on the British for the contribution of equipment and materials.

The intelligence gathering was phenomenal throughout the war where II Bureau and the AK made substantial contributions. Polish forced labourers were located throughout the Third Reich working in key installations that enabled the AK intelligence trained operatives to penetrate factories as forced labour. The most vital contribution to allied intelligence was the V1 and V2 programme based on Peenemünde on the island of Usedom. Here, the Baltic cell led by Bernard ‘Wrzos’, ‘Jur’ Kaczmarek and later Stefan ‘Nordryk’ Ignaszak penetrated the island as forced labourers (Kochanski, 2012). Agents were in 17 ports reporting on shipping movements, naval ships armaments, coastal defences and minefields. These reports also included a new ‘snorkel’ system devised by the Germans for their U-Boat fleet. Agents were also located in German aircraft factories based in Poland at Mielec, Rzeszów, Poznań, Bydgoszcz and Grudziądz.

By February 1944 there was a shift in the strategic planning of intelligence where the need to strengthen links with the Japanese, Swedes, Hungarian and Finnish intelligence services. Poland had long established links to Japanese secret service due to Japan’s rivalry and conflict with Imperial Russia and continued throughout World War II (Pałasz-Rutkowska and Romer, 1995). The shift might be attributed to the turning tide of war after the defeat of the Germans and their allies at Stalingrad fought between August 1942 to February 1943. The Hungarian Army had been decimated and the political fall-out resulted in secret negotiations for armistice with the allies through US and British intermediaries that resulted in the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944. SOE had also implanted Polish operatives disguised as British Liaison Officers (BLO’s) via Slovakia in Operation Desford and Windproof to strengthen intelligence gathering. (Link to Operation Desford and Operation Windproof).

Station T in Jerusalem and Bałk in Istanbul began to develop radio intelligence in the Middle East directed at the Soviets (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005) and the degree of penetration due to activities of diplomatic and consular posts, trade missions and the Soviet press. Due to the potential degree of penetration, II Bureau were asked to investigate French, Czechoslovak and Yugoslav representatives. Such was the threat that in May 1945 plus the impact of the Poles betrayal at Yalta that heads of stations were ordered to study the feasibility of new underground intelligence units not linked to Polish diplomatic missions. By June 1945, existing stations were ordered to ‘decouple’ any ties and destroy all codes, records and equipment. Laboratories and equipment had already been relocated to clandestine locations. II Bureau was ready for post- war intelligence activities at the end of July 1945.

II Bureau also oversaw the Airforce Intelligence Department whose prime task was to assess materials relating to the Axis air forces. The department consisted of four sections: L-1 West led by Lt. Col. Ferdynand Bobiński, L-2 South led by Major Józef Kiecoń, L-3 East led by Major Olgierd Cumfit and L-4 Technical/ Industrial led by Major Stefan Szumiel (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005). Their operations were covered by II Bureau’s intelligence stations and cells in cooperation with the allies counterparts.

Naval intelligence was run by initially by Commander Brunon Jabłoński, then Commander Karol Trzasko-Durski at the Polish Naval Headquarters. The degree of collaboration was marred by differences between British and Polish objectives and the lack in need for parallel organisations which meant an independent operation was designated for post-war activities. However, it was recognised by the General Staff that Polish naval intelligence was necessary and therefore became subordinated to II Bureau of the Polish General Staff. Collection of intelligence was via existing networks of statins and cells based on: Section 1 Germany and occupied countries on the Atlantic and Baltic coast, Section 2 covered the Mediterranean and Section 3 covered all other countries. Like other departments, assessment and research into materials associated with naval matters formed much of their work. The II Bureau opposed use of separate codes or operational independence much to the chagrin of Commander Czesław Janicki (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005). The department was also affected with the relocation of experienced officers and the trimming of training courses impacting on the quality of officers operating in individual stations and the Home Army that was compensated by bravery and sacrifice (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005).

The training programme based in Glasgow consisted of three elements: theory, objectives and organisation of intelligence. The programme included background on the Third Reich, its structure, armaments industry and the military including the Gestapo plus the current situation in occupied Poland. The training covered photography and micro-photography for transmission and forging documents; chemistry for inks and poison or falsifying documents and radio communications that included coding. Practical skills in driving various transport and breaking locks were also included in the intelligence curriculum. SIS officers from British intelligence gave special sessions on intelligence, diversion and sabotage as preparation for deployment abroad.

Intelligence gathering was screened by the Records and Studies department for assessment prior dissemination to the Allies that included both military, economic and political information gathered by the stations, cells, émigrés, Polish Diaspora, escapees, media and collaborators with the Abwehr. The ability of the Poles to collect and analyse an array of information from multiple sources and geographic location has stunned historians in their post-war analysis of Poland’s contribution.

The AK Intelligence Service & II Bureau

It was recognised from the outset that a government in exile needed regular communications with any military or civil organisations during the occupation by Germany. The Polish Government in exile through its Home Affairs Office appointed General Kazimierz Sosnkowski in November 1939 to bring together various political factions under one committee. The result was the Union of Armed Struggle (ZWZ) that also worked in parallel with resistance groups in France who had established their own intelligence service (Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005). Each organisation (SZP, ZWZ and AK) employed different working methods and aims making the role of II Bureau more complex.

The Home Army (AK) constructed its intelligence network from scratch directed initially by the AK’s General Head Quarters. The aim of the offensive intelligence was to prepare for armed operations, diversion and sabotage that included the eventual uprising. It was subordinated to the Polish Government in Exile and worked closely with II Bureau. In the early years, there was some duplication prior to the fall of France, but by and large the fledgling AK was observing the German activities in key Polish cities and in the Soviet occupied zone. In mid-January 1940 General Sosnkowski had a general plan drawn up that by March was operational in the organisation, working methods, tasking specific units and strengthening networks inside Poland. With the fall of France and the decampment to London, it was clear that the II Bureau and British intelligence needed to support the development and improve the effectiveness of intelligence gathering in Poland in relation to the military in Poland, the war industries of the Third Reich and its maritime industries that also included war preparation against the Soviets and an Eastern Front. By January 1941 General Sosnkowski saw the need to separate intelligence structures in Poland between stations conducting deep penetration and operating outside Poland to remove conflict within the AK. (Link to Home Army & SOE/ Government in Exile).

The equipping and provision of funds for operatives and information was the responsibility of VI Special Bureau that managed the land communication systems, training of parachutists for infiltration, securing radio communications and acting as an intermediary in all intelligence matters. Operations remained under the control of II Bureau in providing tasks for the AK, analysing intelligence reports that were forwarded to British intelligence. Through the setting up and supporting underground armies through the SOE, the effectiveness of the cooperation was exemplary. The size of VI Bureau was quite considerable with 61 staff at their HQ with another 312 personnel involved in training and including other support bases employed 961 people.

Initially led by Lt-Col. Kazimierz Iranek-Osmecki who later distinguished himself during the Warsaw Uprising and discovery of the V-1 and V-2 secrets, the baton was passed to Major Stanisław Kijak. The department was reorganised in January 1941 and again in mid-November 1942 when Colonel Gano suggested the Intelligence section led by Major Stanisław Kijak and Captain Cybulski moved to II Bureau (Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005).

| Section |

Sub-Section |

Commanded |

Role |

| Intelligence |

None |

Major Stanisław Kijak. SIC: Captain Cybulski |

Gathering offensive intelligence |

| A Office |

None |

Major Stanisław Kijak. SIC: Captain Cybulski |

Courier Communications |

| Office ‘S’ - Special Operations |

None |

Captain Jan Jaźwiński |

Air drops/ Bridges

Cichociemni |

| Organisation & Operations |

Organisation Information Ciphers |

Lt. Col. Wincenty Sobociński

Major Stanisław Kijak 2nd Lt. Stefan Jagiełło |

Co-operated with AK intelligence

maintaining personnel records with real

and code names, military ranks. Operational

security, guidelines, instructions on underground

tactics, technology and safe houses.

Preparation of couriers and all military communications with bases in Poland.

|

In January 1943 II Bureau changed the way they worked. Signals from AK HQ were passed onto II Bureau after decoding by the VI Bureau. Much intelligence was also delivered through couriers who criss-crossed Europe by any means of transport since the air-bridges were expensive and operationally difficult (Peszke, 1980; Nowak, 1983; Koskodan, 2009). However, these reports and copied documents would go direct to the Commander-in-Chief and the Chief of General Staff with copies being subsequently passed to the Chief of the II Bureau for analysis and translation before delivery to SIS with extracts being passed onto the Polish PM and other interested parties including SOE (Nowak, 1983; Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005). Accounts on the lives of couriers are exemplified by Jan Nowak and Jan Karski’s memoirs that give great insight into AK operations and courage, even under interrogation that makes modern thrillers look ‘thin’ in comparison (Garlinski, 1981; Nowak, 1983; Karski, 2012).

VI Bureau supported the AK GHQ intelligence by transferring intelligence officers, funds and equipment that was financially supported by the British to the tune of $2m alone in 1944 with an additional $4.5m allocated to diversionary and sabotage operations carried out in Wachlarz (Eastern Front) to hinder the German war effort (Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005). The total AK budget was $30m.

With the success of Operation Husky (invasion of Sicily), the decision to invade the Italian mainland took shape over June to August 1943 under the guise of Operation Avalanche with landings at Salerno, Operation Baytown (Calabria) and Operation Slapstick (Taranto) that presented new opportunities for Office S. Captain Jan Jaźwiński was tasked with developing air support that from August 1944 was taken over by Lt. Col. Marian Dorotycz-Malewicz (SOE code name: Colonel Hańcza or Roch) who based the air support operations Brindisi at Base 11 (Polish HQ) in Latiano. These operations were closely linked to SOE activities by Force 139 commanded by Lt-Colonel H.M. Threlfall at nearby Monopoli. Force 139 was tasked to support Polish and Czech resistance movements between 1943-1945 (Foot, 1990; Walker, 2008).

Brindisi became ‘home’ to the Italian Provisional Government led by King Victor Emmanuel III after the allied landings and expulsion of Mussolini. It also became the home-base for Special Duties Flight 1586 (formerly ‘C’ Polish Flight) that had once been based in Tempsford and had achieved 64 missions to Poland with some degree of success with 105 agents and 42 tons of supplies (Walker, 2008). On 1st August 1943 the flight had six serviceable Halifax’s’ and three liberators with the requisite crew that would be bolstered by other planes and crew for the ‘retaliation’ flights to support the Warsaw Uprising (Cynk, 1998).

The Polish Section (headed by Lt. Colonel Harold Perkins) of the SOE worked closely with II Bureau that was in breach of the protocols set out in the Polish-British intelligence agreement of September 1940 which led to strong protests by SIS that led to rivalry and tense relationships at the expense of the Poles (Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005) even though the Director General of SOE, Colin Gubbins had a close working relationship with Colonel Gano, Chief of II Bureau. The level and contribution by the AK Intelligence was dependent upon the needs of the Government in Exile and the need to fund the network to obtain information.

Between 1941-1944, 346 parachutists made up of 315 soldiers many of who were Cichociemni and 34 intelligence operatives, 1 female soldier, 28 political couriers, 1 Hungarian and 5 British were transported to Poland from basses in Britain and Italy. Over $34m in notes and gold was delivered. Additionally, 1775 pounds sterling gold, over 19m German Marks, 569,800 in Polish occupancy currency and 10,000 Spanish pesetas (Cynk, 1998, Ciechanowski, 1975; Davies, 2003; Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005). During the period 1941-45, 868 flights of which 585 were successful (67.4%) saw 70 planes, 62 crew and 11 parachutists lost and 10% of the equipment destroyed (Cynk, 1998, Ciechanowski, 1975; Davies, 2003; Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005). The disparity in support for Poland in comparison the other resistance movements remains a contentious debate. However, there is no doubt that after the Yalta Agreement in February 1945 and the rise of Soviet influence, strategic plans shifted and once the invasion plans for Europe were in advance stages of preparation, the need for wholesale armed rising became less attractive (Davies, 2003; Pepłoński and Ciechanowski, 2005; Walker, 2008; Williamson, 2012). What is sometimes overlooked is that the sheer volume and quality of the intelligence gathering by the AK made a significant contribution to the war effort and that the British financial support was critical in its provision despite the breached protocols and strained relationships between SIS and SOE.

Operations of the Intelligence Services of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MSW) and the Ministry of National Defence (MON)

The structure and operations of the intelligence services of the Polish Government in Exile were complicated through other intelligence interests. While II and VI Bureau provided the core framework, other ministries like the Ministerial Committee for Home Affairs and the Ministry of Internal Affairs presented organisational problems. After the fall of France, it was assumed there would be Continental Action and the Poles were well placed due to the diaspora particularly in northern France. Jan Librach who had been attached to the embassy in Paris, was tasked with setting up an HQ and field stations at the behest of the Ministry of Internal Affairs under the guise of POWN or Polska Organizacja Walki o Niepodległość initially led by Aleksander Kawałkowski (Huberti>) (Drweski, 1987; Pepłoński, 2005). The ‘story’ of POWN, Adjudicate and Monica can be found on the following pages Adjudicate and Monica. and indicates the complexity and overlap between II and VI Bureau, SIS and the Polish Section (MP and EU/P) in the SOE which acted as the fourth arm to the intelligence services. (Link to Poland and the SOE).

Britain formally withdrew the recognition of the legality of the Polish Government in Exile on 6th July 1945. The charade of ‘free elections’ in Poland was to follow with the imposition of Communist Government and the onset of the ‘Cold War’. The final insult was with recognition of the new regime’s sovereignty by the Allies, left the Poles-in-exile in effect a mercenary force. Each of the armed services was responsible for the de-mobilization and transfer of armed combatants into the Resettlement Corps (PRC). An Act of Parliament was passed in February 1946 and in the middle of March, Ernest Bevan formally advised all Poles could not be maintained in Britain (Cynk, 1998). The winding down of the Polish Intelligence Service is not documented, however the knowledge and expertise remained of use to the newly established Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that had been formed out of the ashes of the OSS in July 1947 to face the threat from the newly established ‘Iron Curtain’ countries and the Cold War. (Link to Polish Resettlement Corps).

The role of the Polish Intelligence services in the immediate post war period were governed by the results of the Yalta Agreement, Official Secrets Act and the need to understand that during the post war period Poland suffered a civil war. Operation Wisla was a dark secret until recently kin the West (Link to Polish Autumn). The civil war in the post-war period and actions by WiN was relatively unknown and a risk to all those involved. President Bierut, now head of the communist regime in Poland professed opposition to the ‘Trial of the Sixteen’. He had conveniently abdicated responsibility through the Osóbka-Morawski – Molotov agreement (which allowed First Secretary Gomulka to take responsibility), but unconditionally supported the show trials of General Stanislaw Tatar and former AK commanders and members of the Catholic Church. He had realised while head of the Polish Committee for the National Liberation (PKWN) that all opposition needed to be quashed and control the population. Such was the enthusiasm for the neo-Stalinist show-trials and deportment that Poland replicated the gulags of the Soviet system (Applebaum, 2003). This threat remained real with any opposition to the regime dealt with harshly through imprisonment (in former legacy concentration camps from World War II), particularly after opposition to the 1947 elections. The ORMO, a ‘volunteer reserve militia’ suppressed any opposition and the results of the election had been blatantly falsified with over 80,000 arrested former AK arrested under false charges. The Urząd Bezpieczeństwa (UB) ensured internal security and dissent or any activity towards a true democracy were suppressed.

It was at its worst during martial law until Solidarność posed such a threat that eventually democracy was reinstated after the revolutions across Eastern and Central Europe in 1989.

Deception

Throughout the war Britain had developed a highly sophisticated deception operation that came to its peak during Operation Overlord (D-Day). Counter intelligence or offensive intelligence was part of II Bureau’s activities until it was transferred to the Ministry of National Defence in March 1940. Offensive Counter Intelligence was run by Captain Rudolf Plocek and focussed on assessing foreign intelligence services as well as passing relevant information from the allies back into the field. They also included debriefing ‘burned’ agents and those that may be traitors or fifth columnists. Between 1942 and 1945 there were 138 suspected persons of spying and another 278 newly arrived persons of ‘interest’ passed onto the British intelligence services (Pepłoński and Suchcitz, 2005). The Polish anti-subversive units dealt with the morale of the Polish armed forces, monitored activities of national minorities and communist sympathisers.

Often overlooked, was the role of deception in the overall wartime strategy that Poland had an active part. ‘Phantom’ armies played a crucial role in the deception plan. CASCADE was a long-term and large-scale order of battle deception that the British mastered as a method of exaggerating military strength particularly in the Middle East prior to D-Day (FORTITUDE SOUTH) to deter German plans for any offensive action into the region (Holt, 20005). Poland had three such units:

- III Polish Corps: May 1943 based notionally in Palestine and in Italy by May 1944. In the spring of 1943 elements of the disbanded 6th Polish Division was added to the 2nd Polish Army Tank Brigade that had moved from Persia and Iraq Command in August 1943. The unit was joined by the 4th Carpathian Lancers, 2nd Polish Armoured Brigade (consisting of the 4th, 5th and 6th Polish Armoured Regiments) and 5th Motorised Brigade (consisting of the 7th Polish Field Regiment, 7th Polish Antitank Regiment, 16th, 17th and 18th Polish Motorised Battalions).

- 7th Polish Division formed in March 1943 that had arrived from Russia during the summer of 1942. This was initially a training unit based in Palestine and composed of the 7th Polish Reconnaissance Regiment, 7th Polish Machinegun Battalion, 7th Polish Rifle Brigade (22nd, 23rd and 24th Polish Rifle Battalions), and 8th Polish Rifle Brigade (19th, 20th and 21st Polish Rifle Battalions).

- Twelfth Army: based in the eastern Mediterranean in May 1944.

The deception planning had been exceptionally well carried out in all theatres of war with the Germans and Japanese bought wholesale into the false information, particularly FORTITUDE SOUTH. The evidence is fairly overwhelming when the deception played to both strategic planning and perceptions of the Germans who kept unnecessarily high concentrations of troops in Norway. The Poles played their role in the deception of the Reich.

The role of Polish Intelligence in the decryption of the Enigma ciphers slowly became public in the 1970s after Hindley’s British Intelligence in the Second World War and publications by R.D.M Foot or other operatives like Jan Nowak gave a ‘hint’ to the extent of the operations. Certainly, the existence of different and competing Polish agencies was complicated (Bennet, 2005) that was made more complex by the formation of SOE despite close working relationships and their own special section MP/ EUP. However, the Polish Government in Exile was unique amongst fellow exiled governments and their military support un-wavered throughout the war. The scale of intelligence gathering was staggering considering the operations stretched to Japan, North Africa, Middle East, the Balkans, the Iberian Peninsula and the Americas as well as Europe. Colonel Gustav Bertrand who had been chief of the French II Bureau department of cryptography had run Operation Z had been instrumental in assisting the Polish Enigma cryptology team to escape, published his memoirs Enigma ou la plus grande énigme de la guerre 1939-1945 in 1973 that gave support to the extent and quality of the Polish intelligence service. Access to files and archives was restricted with even claims they had been destroyed. Despite Commander Dunderdale’s report to Churchill appraising the quality and extent of Polish intelligence operations, their contribution remained largely unrecognised to the general public. Stirling and Nałęcz (2005: 562) perhaps summarized their contribution as: It is clear that without the Polish intelligence activity and involvement, the prosecution of the war by Britain and her allies would have been more difficult and protracted. Without their role in the breaking of ENIGMA or information on the V-1 and V-2 weapons, there would have been greater loss in life.

Selected References

Andrews, C. (2005) “British-Polish Intelligence Collaboration during the Second World War in Historical Perspective”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch7.

Bennett, G. (2005) “Summary” in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch58.

Budiansky, S. (2000) “Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II”, Viking, UK.

Ciechanowski, J.M. (1975) “The Warsaw Rising of 1944”, Cambridge University Press, UK.

Ciebanowski, J. (2005) “British-Polish Intelligence Collaboration during the Second World War in Historical Perspective”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch8.

Cynk, J.B. (1998) “The Polish Air Force At War: The Official History Vol. 2 1943-1945”, Schiffer Military History, USA.

Davies, N. (2001) “Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland’s Present”, OUP, UK.

Davies, N. (2003) “Rising’ 44”, Macmillan, UK.

Drweski, B. (1987) “La POWN: un movement de résistance polonais en France », Revue des Étude Slaves, Vol.54, No.4 pp.741-752.

Foot, M.R.D. (1990) “SOE: The Special Operations Executive 1940-46”, Mandarin, UK

Garliński, J. (1981) “The Swiss Corridor”, Dent & Son, UK.

Holt, T. (2005) “The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War”, Phoenix, UK.

Karski, J. (2012) “Story of a Secret State: My report to the World”, Penguin Classics, UK.

Kochanski, H. (2012) “The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War”, Allan Lane, UK.

Koskodan, K.K. (2009) “No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in World War II”, Osprey Publishing, UK.

Nowak, J. (1983) “Courier from Warsaw”, Wayne State University Press, USA.

Mazgaj, M.S (2009) “In the Polish Secret War: Memoir of a World War II Freedom Fighter”, McFarland & Co, USA.

McGilvray, E. (2010) “A Military Government in Exile: The Polish Government-in-Exile 1939-1945, a study of discontent”, Helion & Co, UK.

Pałasz-Rutkowska, E. and Romer, A.T. (2007) “Polish-Japanese co-operation during World War II”, Japan Forum, Vol.7, No.2, pp. 285-316

Pepłoński, A. and Ciechanowski, J. (1995) “The Role of the II Bureau of the Union of Armed Struggle - Home Army (ZWZ-AK) Headquarters in the Intelligence Structures of the Polish Armed Forces in the West”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch9.

Pepłoński, A. (2005) “The Operation of the Intelligence Services of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MSW) and of the Ministry of national Defence (MON), in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch11.

Pepłoński, A. and Suchcitz, A. (2005) “Organization and Operations of the II Bureau, of the General Staff”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch10.

Peszke, M.A. (1980) “A synopsis of Polish-Allied Military Agreements During World War Two”, The Journal of Military History, Vol.44, No.33 pp.128.

Sterling, T. and Nałecz, D. (2005) “Executive Summary”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch59.

Śledziński, K. (2012) ‘Cichociemni: Elita Polskiej Dywersji”, ZNAK, Poland.

Szymanowicz, A. and Gołębiowski, A. (2009) “The beginning of the Second Polish Republic’s Military Intelligence Activity in East Prussia (until 1920)”, Zeszyty Naukowe / Wyższa Szkoła Oficerska Wojsk Lądowych im. gen. T. Kościuszki, No.2, pp.74-86.

Walker, J. (2008) “Poland Alone: Britain, SOE and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance, 1944”, The History Press Ltd, UK.

Williamson, D.G. (2012) “The Polish Underground 1939 – 1947”, Pen and Sword Military, UK.

Winter, P.R.J. (2011) “Penetrating Hitler’s High Command: Anglo-Polish HUMINT, 1939-1945”, War in History, Vol.18, No.1, pp.85-108.

|

|