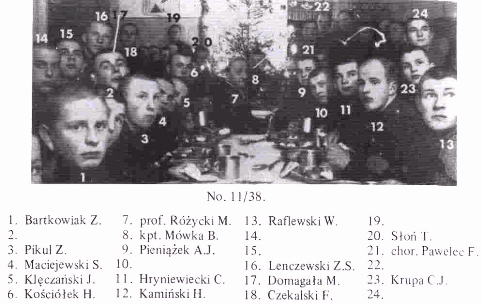

Zenon, Stefan, Teofil Bartkowiak

1921 - 2002

Medals:

French: Combattant Cross, Resistance Volunteer Combattant Cross

Polish and British: 1939-1945 Star, Europe Star, Battle of the Atlantic medal, Defence

Medal, War Medal, Battle of Britain medal, Virtuti medal, Virtuti Military Cross with

4 bars, Silver Cross for Merit with two-edged sword, Air Force Medal with 3 bars.

The following story has been kindly donated by Jan Bartkowiak. All copyright belongs to Jan Bartkowiak and permission is required for any part to be copied. The Bartkowiak family reserve all rights to these materials for any publication including electronic media.

The following story has a particular significance since Zenon Bartkowiak flew missions with my own father Zenon Krzeptowski when they were part of 303 Squadron in the latter stages of the war. Jan has been a great help in translation of web pages and finding materials or other sources of information and generally supporting the role of the website. Forever grateful.

Chapter 1

Introduction

The Boy

Like so many young Polish teenage youths, Zenon Stephan Teofil Bartkowiak found

himself in a most frightening, worrying and uncertain position when on 1 September

1939 Germany invaded HIS Poland. He had already been accepted into a military

flying school to be trained as a pilot but other than for taking a glider course he had

not by then acquired sufficient skills to use in the defence of his homeland. The only

way he was advised to do so by the authorities was to hurriedly leave to reach a

friendly country willing to continue his training so that he could later take up the fight

against those who had overrun his birthplace.

The Young Man

So he set course on an unknown and circuitous journey to reach France and then England. This entailed internment, several escapes and a hazardous trip across several seas before he could reach France, this he did on his 18th birthday and later arrived in England to join the Royal Air Force Despite the fact that he had to pass through

several foreign countries whose languages and customs he neither spoke nor understood, they did hasten his early experience to enable him to become a young man in a very short time period.

The Man

Along with many other young Polishmen with the same aim in life he had to come to terms with the rules and discipline of another country's military arm. This must have been extremely difficult for him to comprehend and assimilate in a short period. He also had to bide his time until an opportunity arose to prove he was worthy of consideration to become a pilot. This took much longer than he had hoped for, but he stuck to his ground crew duties initially assigned to him like a man.

The Trainee

When the opportunity did arise, he soon proved he was capable of becoming a pilot by taking and passing an elementary flying course in England that allowed him to be considered for further training.

The Advanced Student

This involved an advanced course that he undertook as part of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan on a Canadian airfield situated on the vast plains of Saskatchewan. Here almost 3 years after departing from his beloved Poland he achieved his reason for leaving. He proudly returned to England resplendent in his uniform that now possessed his pilot's wings above his breast pocket.

The Pilot

After a spell of flying with battle experienced pilots to gain operational knowledge and technique, he was considered sufficiently qualified to join an operational squadron.

The Squadron Pilot

At last he was in a position to fight and in June 1943 he had been selected to join the second Polish Air Force unit to be formed in England, No 303 Kosciuszko Squadron. This unique Squadron was already famous for its tremendous exploits that lead to its outstanding contribution to the winning of the Battle of Britain. A battle that changed

the course of the war.

He regularly flew with this Squadron on operations across France and the Low Countries in preparation for D-Day under an entirely different name for reasons of his own. Unfortunately he was shot down over Northern France shortly before that momentous day.

The Hidden Pilot

As he parachuted down German ground troops fired at him repeatedly but he was virtually snatched from under their noses by a member of the French underground resistance who became in his own words , "his wartime brother and best friend" . He and others, including a lovely young French girl named Raymonde, knew him only by his new first name "Charly'' and for 4 months they hid him from capture. Later "Charly" became his Christian name for the remainder of his life. When the Allies arrived he returned at once to join his Squadron in England.

The Squadron Pilot Again

So until the end of World War 2 he again participated in 303 Squadron's operations over Europe and was discharged in 1948 with many Polish, French and British decorations gained in the service with the PAF.

The Married Man

In March 1951 he was married in England to the lovely Raymonde who had helped to hide him in France. They had a son and later they all returned to Northern France where they settled down for the rest of their lives.

This is the Story of this Man

The remarkable life story of this man is based on several long letters that he wrote in English in 1994 telling of the time he was in hiding 50 years before. Also several recorded notes came to light of talks that he gave later in life. Surprisingly he left very little other information about himself, so a great deal of research had to be undertaken to complete this story. Much information was found in official records that detailed Zenon's wartime activity. Similarly, little detailed information has been found about Zenon's parent's lives in order to set the background to his own, although his father was known to be a time-serving Polish Army Officer. Both father and son fought in different theatres of war for their respective Polish units and were well decorated for their duties. However, it was more than sad that neither was able or wished to return to their homeland when hostilities had ceased after fighting for so long with this sole purpose in mind. There was no excuse for the injustice metered out by several different authorities after the war that prevented their return and perhaps Zenon's decision to settle in France as Charly, ameliorated to some extent what must have been bitterness and disappointment. Unfortunately his father never had the same opportunity.

This life history has been prepared jointly by his son (a French citizen also with British nationality) and an Englishman (who recorded the history of the airfield Zenon/Charly left when he was shot down). It is not only a tribute to the man himself, but it is also intended to be a record for his existing family today and for those who may follow.

Jan Bartkowiak

Chapter 2

Zenon's Young Years in Poland

His Place of Birth and his Family

Pleszew Family House (pre war)

Zenon Stefan Teofil Bartkowiak was born on 21 day of November 1921 in the town of Pleszew, about 30 km from the German border at that time. It was a small to medium size town with a long history. A large proportion of its surrounding land was arable although there were forests to both the southwest and northeast of the region.

His father was Jan Bartkowiak, born 6 July 1891 at Komorza, Jarocin, Poznan, Poland. He was a regular soldier in the Polish Army from 1919. When WW2 broke out he was believed to be a Warrant Officer in 70 Infantry Regiment who fought in the 1939 campaign in Poland. It is thought he might have been serving in eastern Poland when the Russian's invaded on 17 September 1939. Realising he would be shot if he was taken prisoner by the Soviets and found to be a Polish officer, it is said that he managed to change his uniform for one worn by a dead Polish soldier. He was deported to Russia and probably imprisoned in one of the many gulags (slave labour camps) where Russia placed most Poles that resisted the Red Army's 1939 invasion.

He was thought to have remained in one of these camps until after the signing of the Sikorski-Maisky (Polish-Soviet) agreement of 30 July 1941 after which he was released with others to join the Polish Armed Forces. He re-inlisted in the Polish Army on 1 September 1941 and travelled via Iran and Iraq to Palestine where he arrived on 13 May 1942. He served in 2 Polish Corps in the last 3 countries plus Egypt between 1942 and 1944 after which he saw much action in Italy including the fighting at Monte Cassino and the Battle for Bologna until 2 May 1945. He was finally discharged from the Polish Resettlement Corps in the UK on 5 March 1949. It is said that he became a school caretaker at Worksop in Nottinghamshire during the 1950s. He died in

Zenon's mother was named Malgorzata nee Kasprzak but little more is known of her background.

Zenon had one sister and one brother. It is said that his brother was caught by the Germans listening to an overseas programme on the radio that was an arrestable offence. When his mother was allowed to visit him he requested she bring him food when she next came. This she did but found he had been sent to Poznan and it is said he was later shot. His mother was also shot perhaps as a result of this incident or the Germans found out that her husband was a Polish Officer. His married sister was Janina Borkowska and it appears she also lived in Pleszew throughout the war, as her name and address is given in Zenon's service record as his next of kin. Presumably this would never have been used during the war when Zenon went missing for fear of a German reprisal against his sister.

Zenon Joins the Military Flying Training School

Little is known about Zenon's early life as presumably his father was away from home for much of the time. He obviously became proficient at his studies in order to aim for a career that demanded certain qualifications.

Unfortunately it is not known why Zenon decided to take up flying. Perhaps he was influenced by his father as a timeserving army officer, or he envied him being a military man and with the threat of Hitler wanting to spread Nazism into Poland, Zenon thought it was time for him to act to prevent this. In 1938, at the age of 16 he took the entrance examinations to attend the SPLdM, the NCO's Aviation Training School for Minors at Swiecie, about 160 km north of his hometown. Prospective candidates to this School had to be between the ages of 16 and 17 years and have at least a 7 year of primary school certificate. They had to attend two days of rigorous examinations, be physically fit and possess the recognised aptitude required by the Polish Air Force.

The original School was opened in Bydgoszcz in 1930, but the gathering storm clouds demanded an increase in the number of cadets and a new part of the School was opened in 1937 for first year cadets at Swiecie. The remainder of the School moved to a new location at Krosno in October 1938 that was situated in the south of the country.

His first year consisted of arduous military discipline including drill, better known as 'Square Bashing', physical training and formal learning of military regulations. His standard of education was also upgraded during the year to an intermediate matriculation level. By the end of that year the authorities could select those who would go forward for pilot training. Obviously Zenon was selected as along with other pilot candidates he was posted in 1939 to the military gliding camp at Ustianowa some 60 km southeast of Krosno and only a few km from the famous Bezmiechowa gliding establishment. It is presumed that most who took this course would have soloed and had reached their 'C' badge standard on completion. This type of initial training towards powered flight was of course cheaper and quicker. All were then posted to the main training School at Krosno, about 125 km southeast of Cracow and not far from the Czechoslovakia border.

Parc de la Tete d'Or

by the war memorial in Lyon in January 1940.

The School at Swiecie was closed down in June 1939 due to its proximity to the German border and all sections of that School were transferred to Krosno. Due to the intense pressure to train more pilots and for safety reasons a satellite airfield was opened at Moderowka (known as Krosno Ill) at the end of July 1939 where Zenon is believed to have soloed before September, probably in a RWD 8 type aircraft. This airfield was about 20 km to the northwest of Krosno. During one of the summer camps in 1939 Zenon sustained an injury to his right elbow while taking part in an

athletic event. Exactly what happened isn't known but it left him with a scar that obviously warranted a remark on his service papers when he joined the RAF in 1940.

Krosno Christmas 1938 ‐ what happened to them during the war?

The School had to Close

At the time Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 Zenon was a 17 year old cadet under training. From day one the German Luftwaffe launched divesting attacks on undefended Polish cities, against which most of the out-of-date aircraft flown by the Polish Air Force could do little to stop them despite their brave attempts to do so. This and the German blitzkrieg tactics adopted by its troops and armoured columns. led to a rapid advance into Poland. From the first day of the German onslaught the School's airfields were bombed not once but twice and it is reported that over 60 aircraft out of some 200 on the ground were destroyed and many others damaged. So the Polish Air Force had to quickly decide what action to take, as it was obvious the School could do little to defend itself or help the cause by staying. Far better to save the knowledge and skill of its fledgling pilots by encouraging them to escape to

England or France that had supposedly to come to Poland's aid through a guarantee made on 31 March 1939 should it be attacked. These countries could do little or anything at that point in time so Poland was left to its own devices. If these cadets and their instructors could reach either of these two friendly countries then hopefully they could assist them to complete their training and eventually regain their land by fighting Germany on equal terms. The authorities decided to order them to do just this, but had little idea how it should be achieved and what might lie in their path before they reached them.

Zenon says Goodbye to his Poland

The exact date when the School closed is not known though it would appear to have been before the 11th of that month as initially the cadets and instructors were told to proceed to the USSR, then almost 300 km to the east. When Russia decided to invade Poland on that day, the School then had to change direction and head for Romania. They travelled partly by coach and this means of transport was possibly lost when a German reconnaissance aircraft attacked the party, but luckily there were no serious casualties . During the attack Zenon's party tried to take cover in a potato field where he received a minor wound that he later said was from an anti-personnel bomb that failed to explode. It is said they had to march the remainder of the way. Unlike today, Poland and Romania had a common border at that time and Zenon found himself with his fellow cadets about to enter a country luckily not then under German control. It is

interesting to note that with the existence of today's borders, this escape directly into Romania would not have been possible. It is believed they passed over the border at Kuty.

Few of the cadets could have had any idea of what lie before them and whether any would become future pilots and so help remove those who had invaded their country without reason.

Chapter 3

Zenon's Escape to England

Internment

When the Cadets arrived at the Polish border, thought to be at Kuty, Romanian soldiers met them, any arms they were carrying were taken and all were automatically interned. They were placed on-board a train and transported to Slatina, about 140 km west of Bucharest where they were held in an artillery barracks that were reported to be rather run down and neglected. At this time, the Germans were not in control of Romania for the country tried to declare itself neutral however the fascist influence was becoming obvious and open. For on Thursday 21 September the Romanian Prime Minister Calinescu was shot dead. Fascist of the so-called 'Iron Guard' were captured and executed.

Escape

Some of Zenon's colleagues who were interned at Slatina spoke later of organizations in Romania that assisted Polish airmen, both there and at other locations where Polish military were interned. This allowed the Cadets to gain money and civilian clothes besides acquiring help in how to leave Romania. Most managed to escape internment either by bribery or the lack of strict supervision by the guards. Many headed for the Polish Embassy in Bucharest where their photographs were taken, passports were made and forged visas under assumed names were issued. From there, most made

directly for the Black Sea port of Balcik presumably because someone in the Polish Embassy or a pro-Polish organisation knew that a ship would call there that could take them to France.

Zenon for unknown reasons was not aware of this method for leaving Romania and instead tried to escape the guards at Slatina and make his own way out of the country. Unfortunately he never recorded how. At his first attempt he was soon found by Romanian soldiers who were not averse to firing a few shots at him. His recapture was probably helped by the fact that most of the Cadet airmen had shaven heads and looked more like convicts than Romanian civilians. He tried a second time to escape but this time he left with a colleague. With only the sun to guide them, as they had no

compass, they managed to walk without food for some 24 hours until yet again they were apprehended by soldiers. The third attempt was more successful and was partly aided by, as Zenon later related it, to the illiteracy and naiveté of the guards. Perhaps he gave them the impression that he and others would be back where they were held and hence the guards didn't go searching for them, for few understood the Polish language.

Zenon with a few other colleagues quickly made their way towards the nearest railway line. Shortly after reaching it, a slow moving goods train came into sight heading in the direction of Bucharest and as it slowed even more to take a bend, they managed to board it quite easily. Knowing that the German SS was said to be already in the Romanian capital in some numbers they all wisely alighted before reaching the city. Shortly after, they came across a car that they commandeered and promptly sold it to buy food. The excess cash they hid in their shoes but next morning after sleeping under the large eaves of an overhanging roof, they found their shoes were missing.

Undeterred they walked bare foot until they came to an inn where to their surprise they found it full of escaped internees. After eating once again they took a road to another railway line, found a passing train and gained a free lift as before.

Sometime later they came across a number of farmers talking beside the rail track so jumped off to determine where they were and where they should make for. After conversing in Bielorussian they obtained a ride in a horse-drawn wagon and after a lengthy 5 days walking they arrived at the small port of Balick near Varna on the Black Sea coast. During this time they fed as best they could by scavenging vegetables found in fields and taking fruit from orchards they passed by. Once again, they were taken aback at the port by the sight of a large number of escaped Polish prisoners they found around the harbour. Zenon imagined that he was once again in his homeland as there were so many conversing in the Polish language. He estimated there to be around 1600. The embarkation mainly took place at night by those with so called valid passports and exit visas. When aboard these documents were collected and sent ashore for use by those without them until all those waiting were eventually embarked on the Greek vessel SS "Patris" bound for France.

It is still a mystery how Zenon and his group knew where to head for unless they had heard about this possibility when they stopped at the inn or perhaps had met other pilots or cadets on the way who had prior knowledge. Whatever was the case, it was either very good information or remarkable luck.

The Sea Trip

It is difficult to imagine that some 1600 foreigners could be embarked aboard a modest vessel without raising suspicion. Surely the emigration officials would have become wary of repeatedly seeing Poles with the same passports and visas that were obviously forged, all going aboard the same ship. The emigration authorities at the port as well as the Captain of the "Patris" must have turned a blind eye to what was going on, or say, the Polish/French/English authorities connived to bring this about. Whoever arranged this or allowed it to happen, created a lifeline to freedom for all these Poles who accepted it without question. It was said the ship was a coaler, however from a photo of the "Patris" by Kopanski it does not appear to be a vessel with this type of cargo.

From photos on deck during the journey, published in "Skrzydla" (Nr141/627) by Franciszek Kornicki, the influx of all this additional human cargo had to find its own accommodation wherever it could on-board . Most preferred to stay on deck when the weather was fine during the first few days of the journey but as Franciszek Kornicki wrote later about his first night trying to sleep, his mind was full of what he had seen during his last days in Poland. Thoughts that many others aboard must have been anguishing about. He said he had "visions of his family, smoke rising from burning villages and towns as far as the eye could see, smashed and burned up aeroplanes, smouldering lorries and carts, dead horses and that never-to-be-forgotten hospital in Lodz, full of wounded and dying men, laying everywhere on beds and on the floors, in rooms and in the corridor, some moaning in agony, others lying silently with their eyes closed, or wide open, waiting and hoping." Perhaps Zenon was lucky enough not to have witnessed so many dreadful scenes for he is not reported to have mentioned them, though others who had might possibly have told him about them.

After passing through the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles a fierce storm raged for some 30 hours. Many could not stand the stench of whatever spot they had found below deck, as most were violently seasick throughout the storm. Some went on deck, but while the air was fresh there it became a nightmare feat just to hold on to something to prevent going overboard. It was so incredible that rumour had it that the captain and crew were standing by to abandon ship. Gradually the storm subsided and the remainder of the journey towards Malta was across a warm and smooth Mediterranean. However the drinking water and food ran out some days before it reached the island and six died and around 60 became ill. One report said the stock of wine on board had to replace water, but for a price that the Greek crew demanded. One could imagine what a large number of escaping internees thought of that. A British ship must have known about the passage of the SS "Patris" and the predicament of its human cargo as it was reported that it supplied it with tins of bully beef and water before it reached Malta.

Most Poles disembarked at Malta while a few remained on board while the ship restocked before completing its journey to Marseilles. They did so because they wished to reach France at the earliest opportunity and continue the fight. France had not of course at that time been invaded by Germany. Zenon along with many others preferred to sail from Malta in the 42,000 tonne ship the "Franconia" bound directly for England but in doing so in thick fog the ship collided with another of a similar class shortly after leaving. It returned to Malta for two weeks while repairs were

completed. When it did sail, its destination was changed to stop first at Marseilles where Zenon disembarked and was taken by bus to Lyons-Bron airport arriving there on his 18th birthday on 21 November 1939.

At Lyon he was given a French uniform, presumably, because he was originally a military cadet under training and not yet a qualified pilot. As France was supposedly to come to the aid of Poland, the French authorities assumed he would become a member of the French Army, but this was not to be, although there is no report of what Zenon thought about this.

Zenon at Lyon-Bron 1940

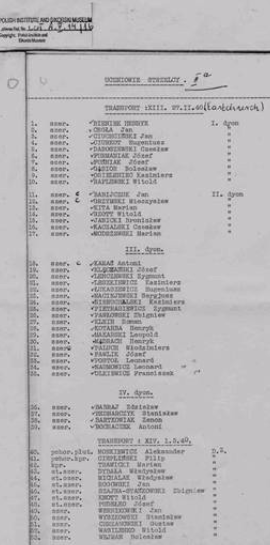

Transfer sheet Lyon-Bron for Eastchurch

Chapter 4

Zenon Becomes a Qualified PAF Pilot

The Ground Training School

When Zenon became officially part of the RAF from 16 March 1940 he was at RAF Eastchurch. This airfield on the Isle of Sheppey off the southern shore at the mouth of the River Thames dates back to 1909. Here much of the very early days of civil flying in England took place and soon after this date it became a military airfield. Up to September 1939 it was in constant use by the RAF, but in December that year it became the destination for the arrival of exhausted and bewildered Polish ground crew. Here the Poles recuperated while being selected for equivalent RAF trades. Many required short conversion courses while others had to be completely retrained. Zenon was categorised as an Aircrafthand Second Class/General Duties, known, as an ACH2/GD. This was the first and lowest rank given to those unqualified in a trade or lacked a skill when first joining the RAF. This was understandable in Zenon's case as

he was still a cadet in training when in Poland with no doubt very few flying hours. Probably his greatest need at that time was to be trained in the RAF ways and rules before his future could be decided. In the month he arrived it is said there were about 1300 Poles at Eastchurch.

With the German rapid advance into France the RAF decided to move this establishment to Blackpool in Lancashire on the northwest coast of England, where it was deemed to be less likely to attack by the Luftwaffe. Here as part of No 3 Wing, Zenon remained from 29 May 1940 to the 1 July that year at what was classed as a Ground Training School that was initially an assembly and clearing centre for all new Polish airmen arriving in England. It is not known whether he became proficient at a given trade during this period or was mainly concerned with familiarizing himself with RAF discipline while waiting what he hoped would be further pilot training. Whatever it was he was no doubt extremely disappointed not to be able to continue with this training immediately, though there is no mention that he showed this.

RAF Bramcote

This airfield northeast of Coventry in Warwickshire was first opened on 4 June 1940 as part of RAF 6 Group and the day Zenon was posted there on 1 July that year the first of 4 Polish Bomber Squadrons was formed known as No 300 ("Masovian"). On 22 July No 301("Pomeranian") was formed and later, No 304 ("Silesian") and No 305 ("Ziemia Wielkopolska") came into being.

When 301 Squadron was formed flying single engine Fairey Battle light bombers, Zenon became part of its ground crew. Unfortunately his duties are not given in his records although there is one indication that he may have become an acting air gunner. The Battle's crew had a pilot, bomb aimer and rear gunner so he may well have acted as a gunner during the Squadron's flying training as before and at that early stage of the war many RAF ground crew acted in this dual role. However there is no evidence to suggest he acted in this capacity on active operations.

RAF Swinderby

Zenon remained with 301 Squadron when it moved on 28/29 August 1940, along with 300 Squadron, to RAF Swinderby, midway between Lincoln and Newark in Lincolnshire, as part of RAF 1 Group. Both were all Polish Squadrons and 301 was

Commanded by Colonel Roman Rudkowski.

Again Zenon's duties are not defined on any of his records but he was on the airfield when both Squadrons made their first Polish operational bomber raid from Britain against Boulogne harbour on 14 September 1940. This must have felt good to Zenon to be able to help in this attack just one year from the time he had to leave his homeland. He may also have been party to the plan to fit wailing sirens to the Squadron's Battles to remind the enemy of what the German Stuka dive bombers sound like on the ground when they rain down their bombs. This was of course wholly unofficial, but no one in the RAF tried to stop them. However on 13 October the Luftwaffe raided Swinderby dropping 6 bombs, damaging 2 Battles and injuring one airman.

During October and November 1940 both Squadrons converted to the twin engine Vickers Wellington. Zenon most probably was there when King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the airfield on 22 January 1941 during a period when both

Squadrons were repeatedly attacking Germany throughout its industrial Rhur and elsewhere. In December 1940, Zenon was promoted to an ACH2, one rung up the RAF promotional ladder.

One unusual feature of Zenon's time at Swinderby was that he was billeted with other ground-crew, away from the airfield. This was sometimes necessary especially on a new airfield before nearby billets had been built. He was placed with a family in Lincoln where the husband was away in the army. The name of the family was Armiger, a name that became of some significance to Zenon in a few years time. It is said that he became like a son to Mrs Armiger who he kept in contact with for many years after the war.

No 12 Initial Training Wing

ITWs were set up to determine whether recruits were likely to be physically and mentally fit to become aircrew. Normally a recruit would have previously been medically examined and taken an initial aptitude test so ITWs could concentrate on the training of navigation, meteorology, aerodynamics, engines and signals. But foot-drill was not forgotten and nor was physical training, all necessary subjects for potential aircrew members.

It is not known whether Zenon had pestered the authorities to continue training to become a qualified pilot, or he was told to wait his time for an opening on one of the normal RAF training courses such as an ITW. Whatever might have been the case he joined No 12 ITW at St Andrews in Fife Scotland on 19 July 1941 and remained there for almost two months. Much of the course was probably familiar to Zenon, as he must have learned much of the basics in Poland prior to September 1939. If as was probable he was told this was the only way he could become a RAF pilot, then in

service parlance "he had to grin and bear it".

No 15 Elementary Flying Training School

At last Zenon was back to flying again for he was posted on 12 September 1941 to join the 23rd course at No 15 EFTS at Kingstown, just 2 miles north of Carlisle, in Cumberland, now Cumbria, during a period when the School was extremely busy. Due to this and the poor drainage at Kingstown, two nearby Relief Landing Grounds were constructed, one at Burnfoot and the other at Kirkpatrick. It is however not known whether Zenon used either of these RLGs.

By 31 December 1941, Zenon had been promoted to a Leading Aircraftman with his records showing his trade to be a ACH/Pilot, though it would have been more appropriate to have been called a Pilot under training.

Early in 1942 the Miles Magister training aircraft, used by the School was replaced by the De Havilland Tiger Moth and a Polish Flight was formed that Zenon presumably joined. The type of training also changed around this time from full ab-initio to flying grading. In the former, students were given some 40 or so hours of flying where many might be flown solo, whereas in the latter only around 12 hours instruction was given. This was considered sufficient to allow students to solo and be judged if they were suitable for further instruction at an overseas School and so save time and money. Obviously Zenon reached the required grading level although his service records show that he remained at Kingstown for almost 4 months that is quite a long time to complete just 12 hours instructional flying time. Perhaps he, along with other Polish students who had some previous flying experience might have completed the full EFTS course, as he later went straight to a Service Flying Training School when he arrived in Canada, rather than completing the EFTS course as did those who were judged suitable at the end of their grading.

At the end of EFTS all students were recommended to become either fighter or bomber pilots. Fighter pilots would go forward to fly single engine aircraft while bomber pilots flew twins. Zenon was obviously recommended to fly single engine aircraft.

The fact that Zenon went to 15 EFTS can in hindsight be considered rather ironic. No 15 EFTS was originally formed as a Reserve Flying School at Redhill Airfield in Surrey in July 1937. At the outbreak of war it became an EFTS and was moved with its Magisters to Kingstown to a safer area for training. In December 1943, RAF Redhill became the parent airfield for the administration of the Advanced Landing Ground at Horne, less than 7 km away, where Zenon would be based in April and May 1944

No 28 EFTS Wolverhampton

Zenon left Kingstown on 17 January 1942 and arrived the same day at Wolverhampton in the West Midlands until the 2 March 1942. The reason why he was posted to another EFTS is not clear although one of his service records suggests that he was part of a Pupils Pilots Pool, presumably to await his next stage of his training overseas.

Aircrew Dispatch Centre

From Wolverhampton he spent a further 10 days at this Centre in nearby Heaton Park at Manchester before setting off on 13 March 1942 from presumably Liverpool Docks for his training in Canada.

31st PD Moncton New Brunswick

(The PD was thought to stand for Pilot Depot.) Zenon arrived here on 27 March and therefore took 14 days to cross the North Atlantic that suggests his ship was part of a slow moving convoy that zig-zagged its way over. Zenon never recorded what the trip was like as storms at that time of the year could be treacherous and enemy U Boats had learned how to hunt in packs by 1942 and many allied ships were sent to the bottom

Many airmen that had been selected for aircrew were regularly taken across by the massive 85,000 tonne Queen Elizabeth Cunard liner that was impressed into carrying some 24,000 service personnel on each trip from the time she was launched in 1940. She was so fast that she had no need of protection and sailed by herself rather than in convoy. Others had to make the journey in whatever space was available in any ship that was allocated. Some of course were lost through U-Boat sinkings and many aircrew lost their lives, like the Danish ship Amerika that had sailed from Halifax in 1943 with 53 trained aircrew aboard on its way back to England. It was torpedoed and only sixteen airmen survived.

Zenon remained at Moncton for 4 days before taking the long train ride across most of Canada to the SFTS where he arrived some 5 days later on 4 April 1942.

No 39 Service Flying Training School, Swift Current, Saskatchewan Canada

This SFTS opened in December 1941 and was part of a massive training programme under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan that came into being in June 1940. This plan allowed training to be undertaken away from the UK where its airfields and skilled instructors were wanted for operational duties and enemy activity could not interfere with training schedules.

The airfield was set within the start of the rolling foothills of the Rockies and Zenon had obviously arrived at the right time of the year because the harsh Canadian winter was almost over as he was thought to have arrived on 13 March 1942. The main part of his training programme would therefore have run into the normally hot summer experienced there. He was obviously there when the following report appeared in the Swift Current Sun newspaper for April 7 1942:-

Interesting Group of Airman Arrive

A group of nearly three score men, a veritable League of Nations, arrived here Friday for No.39 S.F.T.S., of the R.A.F. Among them were Czechs, Poles, Belgians, Norwegians, Free French and British. Some of the Free French in their natty blue and gold uniforms were at the Hospital Aid Dance in Elks hall last night. Among the men who came here are a lot who have had war experiences of interest, some wearing decorations. When they stopped at Moncton N.B., en route, a Free French officer told the Sun, they were told: "Going to be stationed at Swift Current? Your lucky, that's supposed to be a very friendly place." They had an uneventful crossing in a convoy and say: "Others will be following us".

Graduates from EFTS had learned to taxi, take off, climb, fly straight and level, descend and land without difficulty. They had also been taught aerobatics, spins and recovery, as well as low-level flying, instrument flying, night flying and cross-country navigation. SFTSs were created to transfer these skills to more powerful and sophisticated aircraft and Zenon with other students' flew the American designed North American Harvard trainer to gain this experience.

This two-seater aircraft, although possessing one or two undesirable flying characteristics, was recognized to be a fine training aircraft with features akin to the larger and faster Spitfire and Hurricane fighters that students would later fly. These features included a retractable undercarriage, flaps and engine controls. It had a 600 hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine and had a most distinctive note on take off due to the high tip speed of the direct drive propeller, commonly known as the airscrew.

Zenon flew this type of aircraft throughout his time at this School over a period of 5 months according to the demand for fighter pilots at that time and the weather. He would have probably amassed a total of over 100 hours flying by the time he graduated and received his wings. Much of the flying at the SFTS would be solo and he would have been sent on long cross-country trips to test his ability to navigate on his own. The countryside for hundreds of miles around Swift Current was comparatively featureless with very few roads, tracks or railway lines for guidance. The few main features of this vast open farmland included tall wooden grain elevators and most had the name of their location painted on them in large letters. Many a lone flier relying on his own navigation found he was way out from where he should have been when he arrived overhead and read the name.

Zenon's service record shows that he officially became a pilot in the RAF/PAF on 14 August 1942, presumably the day he was presented with his wings at Swift Current, at the age of 21 years. By the 18 August 1942 he had returned to 31st PD at Moncton in readiness to return to the UK.

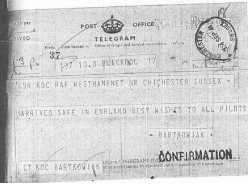

The Polish Depot Blackpool

He arrived at No 3 Personnel Reception Centre in the UK by 11 September 1942 and again no information exists to describe what the return Atlantic journey was like or what vessel he sailed in. By the 30th of that month he took up residence at the PAF depot where he remained for some 4 months. He most probably undertook various courses that might have involved flying, but this would not have been at Blackpool as there was no airfield there. If he was not occupied in this manner then it seems that an awful long time was wasted before he could complete the full course that would prepare him to join an operational squadron.

On 31 December 1942 he was promoted to a Sergeant Pilot.

Veterans' reunion Blackpool.

No 5 (Polish) Advanced Flying Unit

This Unit was stationed at RAF Ternhill, 5 km southwest of Market Drayton in Shropshire. Hawker Hurricanes and Miles Masters were used by the Unit with a large preponderance of the latter. 4 nearby satellite airfields were also used because of the large number of training aircraft stationed there. The Hurricane provided experience on what was still a front line type of fighter. However the Master was considered to be inferior to the Harvard as a trainer but as there were so many of this British designed aircraft still serviceable they had to be used. Despite this both aircraft were used to teach advanced flying techniques.

Zenon was stationed at this unit for only about 5 weeks from 9 February 1943.

No 58 Operational Training Unit.

The airfield on which the OTU was situated was a km south of Grangemouth in Falkirk, Scotland, near the south bank of the Firth of Forth. Zenon arrived there on 16 March 1943 to fly Spitfire MKI and MKlls'. Most Polish fighter pilots trained at this unit before being posted to operational Squadrons. It intentionally exposed pilots to the type of flying expected of them in front line Squadrons. It included much formation and combat exercises as well as gunnery practice.

- 2nd Row at first left: Georges Albert GIRARD († 16/12/1944 "341 Squadron")

- 1st Row at first right: Daniel Paul Eugène FRY († missing 17/03/1944 "341 Squadron")

- 1st Row at 2nd right: Bernard Adrien PÉRAUX († 05/09/1943 "11 AFTS")

- 3rd Row at 2nd left: Ernest Louis LE GOFF († missing 20/11/1948 "GT 2/62")

Part of Zenon's flying training here might have taken place at Balado Bridge a satellite of Grangemouth, about 15 km northeast. This was thought to experience better weather conditions than those on the banks of the Firth of Forth.

By June 1943, Zenon was at last considered to be a fully qualified RAF pilot ready to join a Polish operational Squadron and therefore a pilot of the PAF.

So at the age of just over 21 years, Zenon had achieved his purpose for fleeing his beloved Poland and more importantly he had become a member of his country's Air Force, albeit stationed in another country, to fight those who had invaded his land.

Chapter 5

303 (Kosciuszko) Squadron

RAF Northolt

On the 1 June 1943, Zenon passed through the main gate at RAF Northolt only 9 km from the centre of London to become a pilot of that famous Squadron. It was formed on this airfield on 2 August 1940 at the start of the Battle of Britain and became the 2nd Polish fighter Squadron of the PAF and the first to see action. Within a period of 3 months it proved itself by becoming the highest scoring Squadron in the RAF during the battle. Zenon must have been extremely proud to be posted to this renowned Squadron. Captain Witomar Bienkowski was then the CO.

After completing all the normal joining routine and familiarisation flights as a new boy to make sure that he could recognize the area in which Northolt was situated, his records show that he undertook his first serious flight on 13 June 1943 to take part in a rescue mission off Dungeness on the south coast. It lasted 1 hour 20 minutes and presumably entailed searching for a pilot downed in the English Channel. During that month, Zenon took part in 5 more similar missions in the same area off the south-coast.

During this month of June the Squadron exchanged its Spitfire VB for the mark IXC. This new mark was an improved version of the VB with a Merlin 61 engine and a four-bladed propeller the aircraft was developed specifically to combat the Luftwaffes' successful Focke Wulf 190 fighter that outclassed the VB.

On the 2 July 1943, Zenon found himself taking part in his first operational sortie, the type of which he would become very familiar with in the coming months, known as a Ramrod. As previously explained, this was the operational code word for a discrete bombing raid to destroy a specific target with fighter escort, with 303 Squadron this time providing the escort. The target was Pavilly, north of Rauen in northern France, his flying time was 1 hour 35 minutes, but no details of the actual target or how the operation went were given in his records. The following day Captain Jan Falkowski became the CO of the Squadron.

By the end of July, Zenon had participated in 10 Ramrods and 7 rescues totalling almost 17 hours flying time and by then he most probably no longer considered himself to be a new boy. He was again on some 7 similar missions during August but did not take part in the support for the unsuccessful landings at Dieppe on 19 August when some 62 other fighter Squadrons participated. However he did undertake his first fighter sweep, code named a Rodeo, on 28 August in the Le Touquet area. This was where many of the front line German fighters were once stationed, commonly called the "Abberville Kids", but by this period of 1943 as mentioned earlier, most had been withdrawn nearer to the Fatherland for protection from frequent raids by large formations of USAAF daylight bombers. Such fighter sweeps could consist of up to 36 Spitfires flying together sometimes all in line abreast, either to entice German fighters aloft to fight, or to attack their airfields as well as targets of opportunity. Unfortunately again there are no records as to what happened on Zenon's first sweep.

This might not of course have been his first sweep as sometimes when the escorted bombers were returning home and there was no intelligence that German fighters were in the area, then the Wing or Squadron Leader would be granted permission to leave the bombers and carry out a low-level sweep. On other raids 303 Squadron acted as an advanced sweep to ensure that no enemy fighters would be in the vicinity when the bombers arrived within the target area. One such sweep preceded 36 Marauders on Ramrod 187 on 4 August 1943. Zenon in Spitfire BS 451 was one of 11 aircraft of 303 Squadron along with 316 Squadron. They arrived over Etretat at 19.17 hrs at 26,000 ft and made a dive to the south and then over the Seine estuary. Having been warned of enemy aircraft over Bernay they could not find any so turned NE and were again warned of aircraft over South Rouen but again could not find them, so came home.

Spitfire XIC aircraft flown by Zenon during this period included:-

BS 513 on 2 August.

BS 451 on 4 August

BS 451 on 8 August

BS 506 on 27 August

BS 180 on 31 August

The 23 August 1943 was a memorable day for Zenon because General Sonskowski the C in C of the Polish Armed Forces in succession to the late General Sikorski (killed in Liberator crash off Gibraltar 4/5 July 1943) visited the Polish Wing at Northolt

September 1943 for Zenon mainly consisted of about 10 further Ramrods and so did October, so by 7 November Zenon had amassed almost 57 hours flying time with 303 Squadron. By this month, the Squadron had been operating in front line duties for over 3 years with very few periods of rest in between, so the authorities decided to move it for a spell on the 1ih of the month to RAF Ballyhalbert in Northern Ireland.

RAF Ballyhalbert

Ballyhalbert was located half way along a narrow isthmus-like neck of land that jutted out into the Irish Sea about 20 km south of Belfast. 303 Squadron moved without its aircraft as it took over the LF Mark VB Spitfires left by 315 Squadron when it vacated Ballyhalbert. This mark of Spitfire was a low level version of the VB 303 Squadron formerly had when at Northolt prior to June 1943. It was similar to this aircraft but had clipped wings to enhance performance at low-level as explained in Chapter 2. A few days after the Squadron arrived, Captain Tadeusz Koc DFC became the CO on the 20 November. It was claimed that he was the last Polish pilot to have shot down a German aircraft before hostilities in Poland ended in October 1939.

Patrols

Obviously Zenon took part in some of the convoy patrols the Squadron mounted while at this airfield by the flying hours listed in his service records. Some were to the northeast of Belfast and others were over the North Channel between Ireland and the mainland escorting ferrying flights from the USA. On one or two occasions USAAF Fortresses were lost through lack of understanding of signals made to American pilots to follow 303 Squadron aircraft.

Witnessing the loss of a Squadron Pilot

On 1 February 1944 Zenon wrote a report about the loss of F/0 Podobinski flying Spitfire EN 586 because he was the last person to see him alive on 14 December 1943. The two of them had to return from an airfield at Toome on the northwestern shore of Lough Neagh, some 70 km northwest of Ballyhalbert. Zenon had to collect an aircraft for his S/Ldr as his was unserviceable. At this point in Zenon's report it is unclear how he travelled to Toome and the same remark applies to F/0 Podobinski. Perhaps they flew together in say, a twin-engined communication aircraft. Although

this airfield was primarily used by the USAAF, Zenon says that both 303 Squadron pilots' Spitfires had not been repaired that day 13 December, so they had to stay the night. This suggests that Toome had a major maintenance section that was not available at Ballyhalbert, hence the reason for their visit though this cannot be confirmed as Ballyhalbert was a normal 3-runway standard RAF wartime airfield.

The weather next morning was bad and they were not cleared for take-off before midday. Before doing so they agreed to fly together under the cloud base with the F/0 leading but subsequently Zenon found he had changed his mind when airborne and had climbed above cloud to some 4000 ft. Podobinski called up ground control and while it could hear and answer him, he could not hear control despite repeated attempts to do so. Control then asked Zenon if he could make contact with the F/0, but his gestures indicated that he could not. Zenon estimated that they were some 15 minutes flying time to Ballyhalbert and on contacting control he was informed they were some 5 miles east of the airfield. Zenon then tried to direct Podobinski to follow him by flying in front and across his nose, but he would have nothing to do with it. Perhaps as Zenon said "he didn't wish to obey a subaltern". Eventually he agreed to descend but after two attempts at having to rapidly climb to miss high ground as they came out of cloud, Zenon lost sight of the F/O's aircraft and sought the help of ground control who vectored him to a point where he could descend safely and land.

The weather for the next 3 days was extremely bad and prevented any meaningful rescue flights. On the 4th day a crash site was located on the Isle of Man that proved to be the F/O's aircraft. While this seems a meaningless loss, the question must be asked, 2 "why did he continue to fly on his course for so long? As said above, Toome to Ballyhalbert is about 70 km apart, and Ballyhalbert to the Isle of Man is about a further 50 km, all 3 locations being in an almost straight line. He would have known within a few minutes how long it would have taken to reach Ballyhalbert so why not have made a slow descent on the same course when he thought he was over it until he was either below cloud or over the sea? If he had then flown on a reciprocal course he should have been over land where he might have been able to find the airfield or belly land. One other explanation might have been that something more catastrophic had taken place in the cockpit, be it medical or technical.

See The official statement made by Zenon on the loss of Podobinski

The Squadron is Recognised

Squadron Leader Koc represented 303 Squadron at a luncheon held at the Grand Central Hotel, Belfast on Wednesday 26 January 1944 at the request of the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. The occasion was at his wish to meet representatives of the Allied Forces in Northern Ireland.

Training to Deck Land

Zenon must have flown more hours than were officially listed. For example he has written at some length about the naval pilots who instructed him and other 303 pilots to land on a marked out aircraft carrier. He maintained this was to provide experience for landing in a confined space at night. However, the question must be asked if they were intentionally being trained to use an aircraft carrier while in transit to another wartime front? They used markings on a runway laid out to represent the size and length of an actual carrier. One of the naval pilots stood on the left-hand side of the markings when on the approach and with a bat in each hand signalled to the pilot whether he was too high, too low, to one side, or one wing low, etc. At first sight Zenon and his co-pilots thought it quite impossible to land within this restricted area and told his naval instructors so. To prove that it could be done, the two naval pilots flew one of 303's Spitfires and on every landing made it look so simple. By the end of 10 days practice Zenon and other pilots of 303 Squadron were able to achieve this feat on almost every occasion. They then trained to do this at night with the aid of coloured approach lights. By the end of these training exercises they had become very competent and as Zenon put it, "I really enjoyed the accomplishment".

Restless

Although the Squadron had been posted at Ballyhalbert for an intended rest period it did not seem like that to its pilots as month after month went by. Stationed there during the cold and wet winter of 1943/44, most were more than keen to be back on operations in the south of England. It was most obvious that the invasion of France would take place in the coming months and they all wanted to be part of it. Zenon forcibly expressed his thoughts on this topic well after the war in various letters.

During the first 4 months of 1944, Zenon had only 3 official flights listed in his records, though of course there were no doubt several training flights that were not recorded, or perhaps very bad weather had curtailed flying to a large extent in that location. Morale towards the end of April was likely to have been somewhat low when orders to move back to the mainland were at last received. Not only that, the Squadron was to be based south of London where the action would take place perhaps both before and after D-Day. No one appeared to be concerned that they were going

to an Advanced Landing Ground that implied living under canvas they just wanted to be away from Northern Ireland, back to operational activity and the recreational high-spots of London.

So by Sunday 30 April 1944 all was packed and 303 Squadron was on its way south back to the mainland and action. Zenon was one of the pilots who flew an aircraft southwards.

Advanced Landing Ground at RAF Horne

It was a bright spring-like morning when the Squadron landed at familiar RAF Northolt to refuel and have a bite to eat before proceeding on a 20 minute flight to the southeast of RAF Redhill. Soon the Squadron was in formation over what looked like a giant X that marked out the two metaled grass runways of ALG Horne set in farmland in southeast Surrey. Six young Air Training Corps cadets and the pilot of a De Havilland Dominie on a local flight unintentionally witnessed this scene from above as the Spitfires peeled off and made a stream landing one after the other, one of which Zenon must have been flying. One of those young ATC cadets still remembers that scene very clearly.

The official Ministry plan for the airfield indicated where the tented sites should be located but these were never adhered to, probably because the aircrew of the 3 Squadrons who arrived that day, had their say (See Chapter 2). Instead of placing them well away from the 2 runways as planned the aircrew erected them close by so the distance from each pilots' tent to his parked aircraft was extremely short. Each Squadrons' pilots and ground crew grouped themselves close together but separate from the other two.

Conditions on the ALG were purposely basic to expose both air and ground crews to what it might be like if and when they had to operate on mainland Europe. Several pilots found sleeping like this very unpleasant especially when the temperature fell below freezing. So another use for daily newspapers was quickly found to separate ones body from the earth. Besides living under canvas, ablutions consisted of washing in canvas sinks and baths using cold water. Breaking the ice in order to shave was another unwelcomed exercise.

The 3 Squadrons that formed 142 Wing at Horne were placed under the Air Defence of Great Britain instead of the 2nd Tactical Air Force that was responsible for air operations before, during and after the invasion of Europe.

After just one day to settle in, the Wing was on its 1st Ramrod early on Tuesday 2 May 1944 even though it was part of the ADGB rather than the 2nd TAF. It was a mark of their flying skills and efficiency that the 3 different Squadrons could fly on an operation for the first time within two days of coming together. However, Zenon did not take part on this occasion but he was on one of the patrols next day. The Wing regularly mounted dawn and dusk patrols over 2 areas. One was around the North Foreland near the southeast mouth of the River Thames and the other over the Solent, to the northwest of the Isle of Wight, two important areas to prevent enemy raids during the build up to D‐Day. However as one pilot said "We were never trained to fight at those hours of the day and the Spitfire was not the right aircraft to do so in any case!". This pilot was right as the Spitfire possessed no form of radar and had to rely on a ground controller to vector him to the vicinity of an unidentified aircraft. By this time of the war it had been proved that the most difficult part of a night-time interception was closing in from the last 500 km and this was virtually impossible without electronic aids.

Patrols and Ramrods with sweeps became the main activity of the 3 Squadrons throughout May. Up to 21 of that month Zenon had participated in 7 operations without any known incidents. However other members in 303 Squadron were not so

lucky. Several either brought back damaged aircraft or they lost their tail-wheels on landing due to the start of the runway steel mesh curling up. F/0 Zbigniew Marszalek on a local familiarization flight soon after he arrived, crashed into the ground at Nutley in Sussex, for no apparent reason and was killed. The 21 May was a black day for the Wing, 3 Spitfires were shot down and their pilots taken prisoner while 4 other Spitfires were badly damaged, all it is believed as the result of a low-level sweep after the Ramrod. One taken prisoner was F/Lt Stanislaw Brzeski one of the original Polish pilots in the Battle of Britain who had been credited with shooting down 8% enemy aircraft. This equalled the record of F/Lt Eugeniusz Szaposznikow who was also in the Battle and still with 303 Squadron.

The work was hard, tiring and dangerous particularly having to take off and land in darkness for the dawn and dusk patrols. Zenon believed that without the carrier training at Ballyhalbert, he for one could never have undertaken these patrols with the confidence he then had and often he felt a certain buzz having completed such a flight. However, the living conditions on the airfield did little to compensate at the end of the day's flying in contrast to most of his previous postings. The only thing that made up for this was the closeness of Horne to London where various cinemas, theatres, clubs and bars could be visited one after another. Full use of 24 and 48 hour passes were made in this way, especially by Zenon. In one of his later letters he indicated he had just returned from a weekend in London on Monday 22 May and found he was not on operations that day. Later he heard that another 303 pilot who was, had not returned from his weekend and when Ramrod 909 had been ordered late that day, Zenon was listed to take his place. Not only that, Zenon had to use his aircraft, EN 836 instead of his own. And so Zenon's fate was sealed that day though of course he had no idea what it would lead to.

Chapter 6

Shot Down and In Hiding

It was Zenon's Lucky day

It just so happened that the 22 May 1944 was the day of an important religious event held annually in France, when families and close friends celebrated their children's first communion. Besides the communion, it usually included a party with a large meal, much wine and jollifications that continue well into the night. Even though it was wartime, a party was still underway by early evening as Zenon was deciding how he should abandon his stricken plane high above. At that precise moment one of the guests named Michel Salmon, decided to stretch his legs outside and as he did so a noise made him look skywards towards an aircraft in trouble trailing smoke and falling rapidly to earth. Close to it was the pilot that had just taken to his parachute and was dangling beneath it while swinging from side to side in an attempt to avoid bullets being fired by German soldiers some distance away. Within the next second or two the plane had crashed not too far away from where the pilot was likely to land thought Michel. With his strong connections with the wartime underground movement in France he realized at once that there was every chance of him reaching the pilot before the Germans could if he had some means of transport. Looking around he spotted a ladies bicycle leaning against the side of the house, grabbed it and sped at brake neck speed towards where he imagined the pilot would land. He was not wrong and after finally struggling to pedal across a beat field arrived breathless to find Zenon in a collapsed state cuddling his parachute after his heavy landing.

If Zenon had been shot down on any other day, then he most likely would have been taken prisoner and the rest of his life would have been extremely different.

Whisked from under the German Noses

Zenon sat severely winded from his hard landing in this field somewhere in France with no idea of exactly where he was. His first task was to bundle up his parachute in his arms that he did still sitting on the ground to recover from the shock of his hazardous descent and heavy landing, glad to still be in one piece despite being shot at on the way down. Before he could think what to do next the young paleface man with his lady's bicycle was standing over him breathing heavily in his race to reach him first. Zenon's first words were in very broken French, "Anglais, Anglais. To confirm this he immediately pulled his identity disc from around his neck, it gave his name as Charly Armiger and not Zenon Bartkowiak. The young man knew that the Germans were not averse to dropping one of their own personnel in RAF uniform to find out who would help them. He also knew that many loyal French men and women had been caught in that way and along with their families were not seen again. Having established that he really was a RAF pilot, the young man felt him all over to ensure that he had no broken bones and could stand up to make a rapid getaway. Meanwhile many children had followed the young man across the field and were standing to watch what was going on. Some obviously knew the young man as they called him Michel, so Charly at least then knew his first name. Michel of course also knew Zenon's adopted first name by which he would continue to be known by everybody that he came into contact in France for the rest of his life.

Zenon with his rescuer 1946

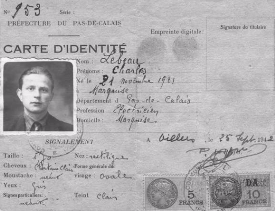

Forged ID card

Michel removed his blouse-like coat and signalled to Charly to put it on. All that Charly wanted at this point was to know where the Germans were? Michel indicated they were in the opposite direction to where he was hurriedly trying to take him towards some bushes at the side of the field. After passing into the next field full of rape, almost at the double, they descended into a shallow ravine known locally as "Le fonds de la noix", or "The bottom of the nut". Here they had to pause for a while as Charly was completely out of breath from the pace Michel had insisted they should move at. During the short stop, Charly took his knife out to cut off the tops of his flying boots to appear that he was wearing ordinary shoes. After burying the tops under bushes with presumably his parachute nearby, they hurried still farther for about one and a half kilometres. This gave the impression they were making towards the woods that Charly had seen on his way down. But Michel changed direction several times, once to divert the children who persisted in following them, once because he took a wrong turning and the last time to turn away from the woods towards the village of Camblain Chatelain. Shortly after, they came across a farmer's pitchfork beside the path and Michel quick minded gave it to Charly and told him how to carry it. This was to give the impression to anyone who saw them of two farm labourers returning home from a hard days work in the fields, as it was after all, well into the evening by then. Every German searching for the downed pilot would have obviously imagined he would head for the woods and no doubt the children confirmed this when questioned, as none would consider them foolish enough to head for the village. In any case it was only the last 60 metres or so that they were visible to others where they had to cross a single track railway line and pass through a cemetery before they arrived in some ones back garden where Michel was known to frequent.

The First Hiding Place

Inside the house was an elderly man sitting at a table in the kitchen eating who became very concerned when he realised what Michel had done. Angry words were exchanged and Charly thought his liberty had come to an immediate end. He had no idea what happened after this as he passed out, partly from the pain he had experienced in the landing and no doubt partly from shock that now set in. When he eventually came too an elderly lady had joined the group and a heated discussion was taking place. While this was in full flow and totally incoherent to Charly, he instinctively reached into his pocket to take out an English cigarette that he lit up. This brought the conversation to an abrupt halt. Michel immediately rushed over in panic, ripped the cigarette from Charly's mouth, removed the packet from his hand and threw both into the fire. He rapidly explained that such cigarettes had a most distinctive smell compared to normal French-made cigarettes that others could easily recognise including Germans. Charly learned later that the two elderly residents who were in effect Michel's adopted parents, were angry mainly because he had not retrieved the parachute. When this was later found, the number of bullet holes were counted before pieces of the silk canopy were shared among the villagers. It was found to be 44! It was a wonder the canopy had not split apart before he had reached the ground, after all that was one of the purposes of the Germans gunners because it was an easier target than trying to hit the pilot swinging beneath. Both were of course not allowed under the Geneva Convention. This might have caused him to descend faster than normal and why it made his impact with the ground that much heavier.

The foreign currency that Charly carried on all flights over enemy territory was also given to his rescuers for safekeeping. It included British, French, Belgian and Spanish notes issued to gain possible aid to escape. His stomach was still not right for he vomited badly after drinking a most welcome cup of coffee. Nevertheless he had to be found a safe house for the night and he was asked if he could ride a bicycle. After donning other French workers clothing given by the elderly man, the two of them rode across to the other side of the village to Michel's own house where he spent the first night.

Before doing so, Michel started to cook them a meal. He had obtained some ham from the black market and wanted to fry chips to go with it but as the fire had not been lit for some time the kitchen soon became full of smoke. Despite Michel's persistence Charly recalled that the meal was however not very tasty partly because he was still suffering from his heavy landing and partly from the effects of delayed shock.

The German Search

The Germans arrived in three armed motorcycle sidecars to the spot where Charly had landed some 15 minutes previously. They vigorously searched the immediate area and the nearby woods for several days before deciding to widen the search to include the village, as they had no clues as to where the fallen pilot might be hiding. Michel a

widower, was at the time courting a nearby widowed school teacher named Genevieve who had two young girls named Paula and Jacqueline who were to become the eyes and ears for Charly. Suspecting that the Germans would start to search the

village, Michel hid Charley in the local cemetery in a vault where bodies were held before burial. He was first taken there in the dark so he had no idea who he was sharing his hiding place with until it was daylight. Michel stayed with him during the first night there but had to depart around 4.30 am before dawn so as not to be spotted during curfew hours returning to his own house before reporting for work at the local coal mine. Charly recalled later how scared he was when left alone especially when he realised there were two bodies alongside him in the vault awaiting burial. One had a well‐made suit on that he estimated would fit him perfectly but he was too nervous to take advantage of it.

Later that afternoon Michel appeared looking very dirty and grimy from his shift at the mine to say that he would go home to wash and return later with some food. This he did with two slices of fresh bread and cheese as miners received increased rations from those of ordinary workers. Alas, Charly's stomach had not yet settled enough for him to enjoy it, but he did rejoice to have company once again.

When not working at the pit during an afternoon, Michel worked with a very pretty hairdresser named MM Raymonde Lavin in the house of her aunt named Marguerite. This aunt, who was the half sister of Raymonde's mother, had adopted her after her 20 year old son had died in a motor cycle accident. Knowing Raymonde well and that she spoke fairly good English, Michel wanted to share his secret about Charly with her. He opened the conversation talking about the "umbrella", meaning parachute. He went on to tell her that he had the other end at his house and asked if she would come along to speak with him. This she agreed to. She had learned her English during the 1939/40 stay of RAF officers who visited her Aunt's Cafe next to the hair saloon where she worked. (They were thought to have been based on the airfield at Bethune/Labuissiere .)

At last Charly could converse with Michel with some understanding via Raymonde whom he became very attached to. They would meet at different locations mainly after the curfew hour of 7 pm. Raymonde would use her bicycle and not be too

concerned to be out after the curfew hour as many German officers used her saloon and knew her well. A pretty young lady with a sick aunt that she was supposedly visiting seemed to be accepted by those who stopped her. At these meetings the three of them would arrange where Charly would be hidden with always a reserve and an emergency location in mind. Also if possible to have the two young girls playing nearby to act as a look out for whenever Germans were around. If Germans were in the vicinity they would sing certain songs in the street to warn Charly who, if it became dangerous, he would make his way to the next arranged hideout. On one occasion they sang extremely loudly and it became too late for him to move quickly as the Germans were close by making a house to house search so he had to make for the emergency hiding place. This was at the bottom of a garden close to a shed containing goats and rabbits where there was a deep well with a heavy hinged grill on top. Below the grill was a pipe used to pump the water up. Luckily the pipe had a collar every so often, presumably a joint, so he could place his feet on them and clasp the pipe with both hands. The two German soldiers who searched the property he had been hiding in decided to enjoy a cigarette at the bottom of the garden so came to the well to do so. Before leaving one decided to relieve himself so urinated down the well much to Charley's discomfort! He could not of course utter a sound, but once again he had been saved.

Two young French girls who sang to Zenon while in hiding

The Need For A Move

After a while, Michel became anxious because several villagers were talking discreetly between themselves about the RAF pilot that Michel had saved. He became frightened that someone would overhear this type of concern, so he decided that Charly should be hidden from then on, away from the village. He was also concerned about the number of people who knew in detail of what he had been up to and what might happen if the Germans decided to question them.

Michel with his knowledge of various resistance groups knew they had their own special methods so he arranged a meeting through a woman with two men from Arras in a hairdresser's shop called "Serge". They worked with a group who specialised in helping RAF crews to return to England. A third man arrived late, he being a Gendarme made Charly somewhat worried mainly because of the uniform so he asked to see his papers. Not only did the Gendarme produce them, but he also handed Charly the gun from his holster. Michel assured him that it would be alright, but Zenon decided to stay with Michel and the three men returned to Arras. It was only when they had driven away did Charly realize that he still had the gun.

Raymonde had a friend of Scottish descent whose father named McLeod had been caught hiding a British soldier. He also had a radio transmitter and had acted for the intelligence service. He was taken to East Prussia where he died. The mother was taken to a Polish prison camp but survived the war. They had a son and two daughters who all worked in the mines and lived at St Pierre les Auchel. The eldest daughter was taken to the Gestapo prison at Loos and severely tortured in order to find out if others were involved. Eventually she was released with photos of her ordeal that she

was ordered to show her sister who they said would endure similar punishment if any of the family were caught hiding wanted individuals. Charly was to be hidden by the elder sister and he was to be taken there by Michel in daylight. By this time Charly was sure that he would be stopped due to the frightful looking clothes he was wearing. Also if stopped wearing civilian clothes he knew he would automatically be shot as a spy.

Despite these worries the two of them set off next day towards St Pierre. Michel walked a few steps in front of Charly following on behind, using a stick, complete with beret and a hand-made cigarette dangling from one corner of his mouth. At one point they rounded a bend in the path alongside a wheat field and to their utter amazement and horror they were confronted by a patrol of about 14 or 16 well disciplined German soldiers. Michel walked straight on without batting an eyelid, so Zenon followed with a stern glare on his face and the high-tension danger was over in seconds. Eventually they arrived in front of a block of terraced houses where many grim looking men and women were talking. They had obviously just come from a shift at the mine. After lingering among the group for a while, the two entered one of the houses and was immediately met by a pleasant rather plumb girt "Hello Charly" she said, "I'm pleased to meet you." "I'm a good friend of Raymonde, we went to school together. So don't be afraid you're in safe hands and you'll spend a few days in this house." She then went on to explain with some authority "that he could not leave the house and had to stay in the loft at all times. Unfortunately the loft had no windows and the only light was a 15 watt, 110 volt bulb, but she did provide a bucket, a small wash basin with the minimum of water and a tiny amount of miners' soap that reminded Charly of a piece of stone covered in glass paper. However she promised to visit him every day. She went on to say "that tomorrow everyone must be out on the main road to greet Field Marshall Rommel as he passes on his way to the Normandy front (therefore it most likely was after D-Day, 6 June 1944). However, a man will fetch you called "79" to have your photograph taken for your identity card to be prepared. Tomorrow will be the best day as all German soldiers as well as the Gestapo will be engaged in providing security for the Field Marshall.

Mr 79 duly appeared and they marched off together trying to give the impression they were in deep conversation but Charly had no idea what he was talking about. The photo was quickly taken and they returned while all the crowds were still on the street. He recalled how pleased he was to return to the house to use the bucket! Several days later Mr 79 arrived with Zenon's identity card. The stamp on the photo was made from a raw potato skin and to Charly he thought that it looked far from the real thing. He had been given the name of Charles Leblanc, born somewhere in Bretagne. 79 obviously noted Charly's dissatisfaction because a few days later he was given another. Charly's name this time was Charles Lebrun. Although the standard of the card was better than the first, Charly thought the stamp was still very poor and it would never pass German inspection.

79 also became concerned about Charly's shoes that on close inspection could be seen to have been cut down. He said he knew of someone in a village about 8 km away who could provide a pair but would not do so unless he actually met the person. It was raining hard, so 79 suggested they should make the journey walking across fields' as it was less dangerous. Charly quickly agreed if for no other reason than to be out of the loft breathing fresh air. Eventually they arrived at a small shop that sold almost anything one wanted. The man inside looked Charly over very carefully, went away and came back with an almost brand new pair of working shoes that fitted perfectly. There was no conversation whatsoever between all three and the exchange took place in just a few minutes before they were on their way back.

Charly later said that 79 was a pleasant man around 60 years of age who he later was told had been shot dead on 1st September 1944 close to the spot where both had crossed the road to have his photograph taken. He was buried locally and Charly often visited his grave after the war.

Yet Another Move